The 5 Best Evidence-Based Supplements For Anxiety

The 5 best evidence-based supplements for anxiety include passionflower, kava, St John’s wort, L-arginine, and magnesium, according to recent research.

The deeper I dive into health and wellness, the more I’m convinced that the “settled science” we’ve swallowed whole is a house of cards. Red meat? Turns out it’s a nutritional powerhouse, not the villain we’ve been sold. The food pyramid? More like a flipped-out fraud. And now, fiber’s getting the same wake-up call—time to rethink what we thought we knew.

Mainstream dogma swears fiber’s the holy grail—digestion, cholesterol, blood sugar, gut health—all supposedly crumble without it. This article’s about to flip the script on the slowly fading mainstream narrative, armed with a surge of real-world stories, cutting-edge peer-reviewed data, and my own zero-carb, zero-fiber experiment (I thrived like never before, with one caveat we will soon see).

Sure, it’s not one-size-fits-all—fiber’s got its perks for some. For those with a terrible diet high in carbohydrates and sugar, fiber will offset damaging insulin responses. We’ll unpack it all, no stone unturned. By the end, you’ll either rethink everything or at least walk away sharper than you came.

While we’ve heard our whole lives that fiber is essential, few know what it actually is.

Fiber is a complex carbohydrate made up of long-chain sugar molecules found in the cell walls of plants, comprising a variety of compounds like cellulose, hemicellulose, pectin, and lignin.

Unlike digestible carbohydrates, such as starches, fiber has bonds between its sugar molecules that human digestive enzymes cannot break down. As such, fiber is, by definition, indigestible by humans.

But don’t be fooled: just because it’s a no-go for our gut doesn’t mean it sits there doing nothing. There are two types of fiber, soluble and insoluble, that interact with our digestive system in different ways.

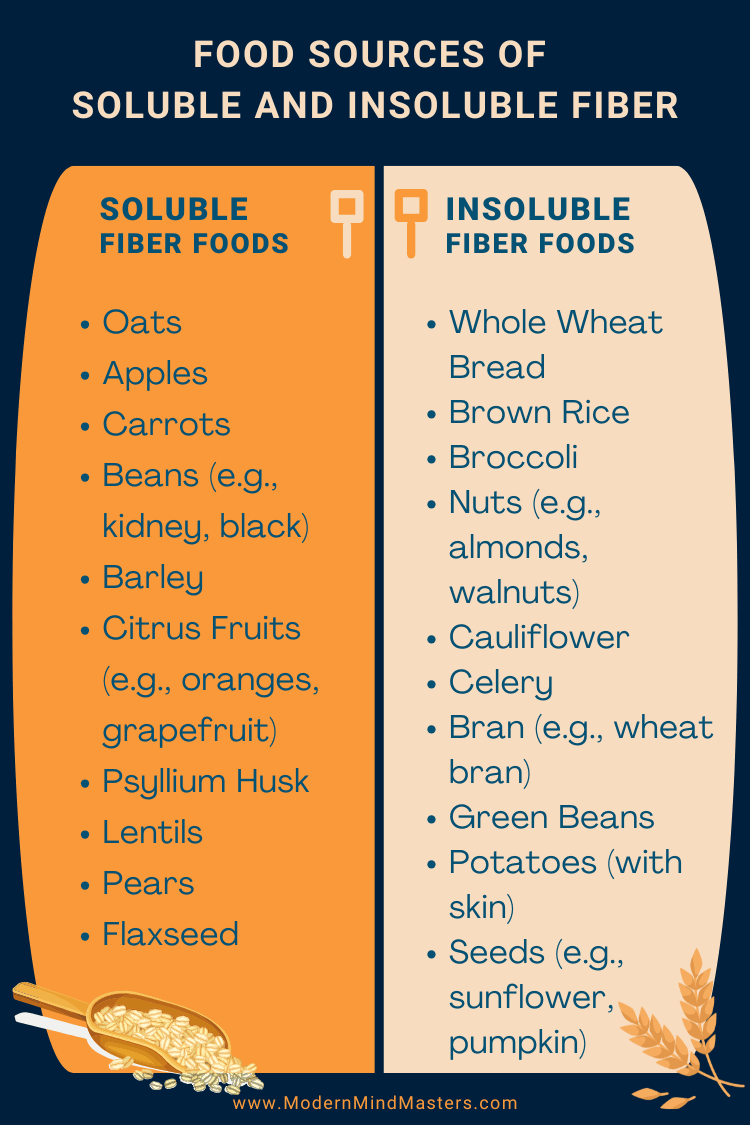

As the name suggests, soluble fiber (e.g., pectin, gums) dissolves in water and can form a gel-like substance. This type of fiber is usually found in oats, barley, beans and legumes, fruits, vegetables, nuts, and seeds.

When soluble fiber enters the digestive system, the gel-like substance made in the stomach and intestines slows down digestion. As a result, soluble fiber has a regulating effect on blood sugar levels while increasing feelings of fullness.

As it moves into the large intestine, gut bacteria ferment soluble fiber. During this fermentation process, short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as butyrate, acetate, and propionate are produced. These SCFAs provide energy to colon cells, support gut health, and have potential anti-inflammatory and metabolic benefits. While these are indeed good for general health, they are not without drawbacks and downsides that we can sidestep by scoring those same molecules smarter, as we’ll unpack soon.

Insoluble fiber does not dissolve in water and remains largely intact as it moves through the digestive system. Due to its inability to break down, it adds bulk to stool, supposedly helping to pass food more quickly through the stomach and intestines, in theory promoting regular bowel movements while preventing constipation.

Common sources of insoluble fiber include whole grains (like whole wheat and brown rice), nuts and seeds, vegetables (especially the skins), cauliflower, potatoes, and dark leafy greens.

While these indigestible molecules will certainly add bulk to stools, I can attest, however, that fiber is not necessary for regular and effective movements. As someone who switched to a diet with zero fiber or carbs for over a year, I’ve had perfectly regular bowel movements without any issues. Before, on a higher-carb and fiber diet, I was still regular but had to poop two to three times a day. Now, this is once a day without fail.

One of the most common myths I hear about fiber is that it is an “essential nutrient”. This is false on two counts. Firstly fiber is not a nutrient – nutrients are typically defined as substances that provide energy, support growth, or are essential for bodily functions. Since fiber is indigestible by human enzymes and doesn’t provide calories or essential nutrients, it doesn’t meet the definition of a nutrient. Fiber is simply a carbohydrate.

Secondly, fiber is not essential. Unlike other essential elements like vitamins and minerals, fiber is not required for basic survival. Having been thriving on a fiber-free diet for at least one year, I, like many other keto advocates, can positively say that fiber is not essential.

I’ve also heard the argument that not eating fiber may be tolerable in the short term but potentially harmful in the long run. While I personally struggle to believe this from a logical point of view, and I can’t see any mechanism for why this would be, it is true that there are no studies on the long-term health effects of not eating fiber. Anecdotal evidence of long-term ketogenic dieters is all we have (which is mostly positive), so keep this in mind.

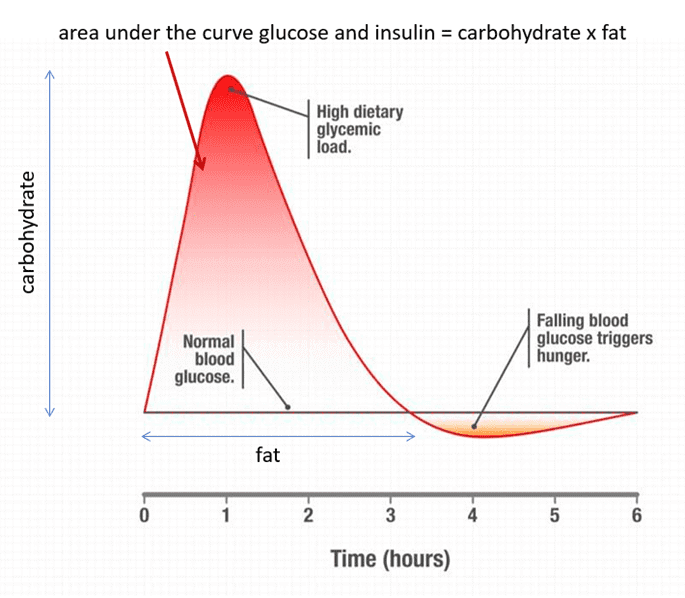

One of the most significant benefits of fiber is its ability to reduce glucose spikes by slowing down the digestion and absorption of carbohydrates, which helps keep blood sugar levels more stable after meals.

Glucose spikes are the silent killers and are usually the culprit behind almost all metabolic disorders, from type 2 diabetes to heart disease.

When consuming carbohydrates and sugars, these molecules break down through metabolism and digestion into glucose, a simple sugar molecule and a source of energy for cells, tissues, and organs. As a result, consuming carbohydrates and sugars causes a rise in glucose.

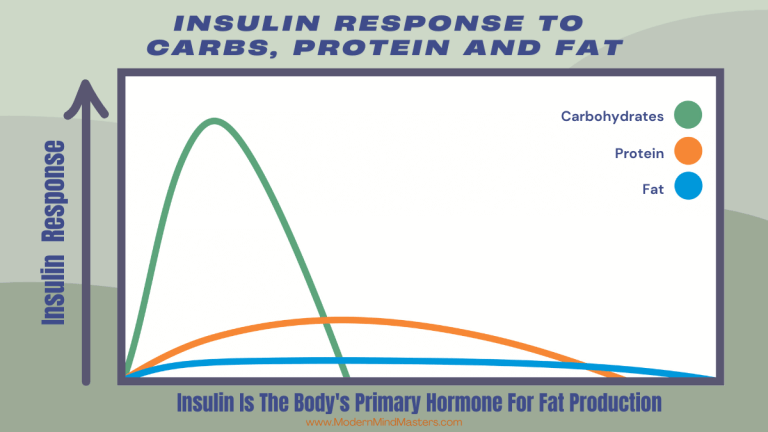

We call this rapid rise in glucose levels a spike. In response to a glucose spike, the pancreas releases insulin, a hormone that helps the body’s cells absorb glucose. Insulin’s job is to bring blood sugar levels back to normal by facilitating the entry of glucose into cells for energy or storage (as glycogen or fat).

If glucose spikes are frequent and excessive (e.g., from eating high-carb or sugary foods often), the pancreas has to release large amounts of insulin each time. Over time, insulin resistance can develop, where the body’s cells become less responsive to insulin, making it harder to bring blood sugar down.

It is this insulin resistance that is the source of so many of the modern world’s chronic health issues. When insulin resistant, glucose stays in the bloodstream longer, causing further blood sugar spikes and further escalating the problem.

Insulin is also a storage hormone. Chronic glucose spikes can lead to increased fat storage, obesity, higher inflammation, and a greater risk of metabolic diseases. From here, it’s just a cascade of compounding health problems that can soon spiral out of control, requiring medications that add further side effects. Not fun.

Hence, fiber is often praised for its ability to reduce both the intensity and frequency of glucose spikes. Soluble fiber absorbs water and forms a gel-like substance in the stomach and intestines, slowing down the emptying of the stomach and the digestion process. As a result, sugars and starches from food are absorbed more gradually into the bloodstream, reducing the intensity of the peak, therefore reducing the insulin response.

This is the only real strong argument for including fiber in your diet – to reduce insulin spikes from glucose. But where is the glucose coming from? If we look one layer deeper, we soon see that consuming fiber to control your insulin spikes is a little like putting a Band-Aid on a leaking pipe.

Similar to how it is better to replace the pipe than keep patching it up, it is better to not consume glucose-spiking foods that require fiber to mitigate.

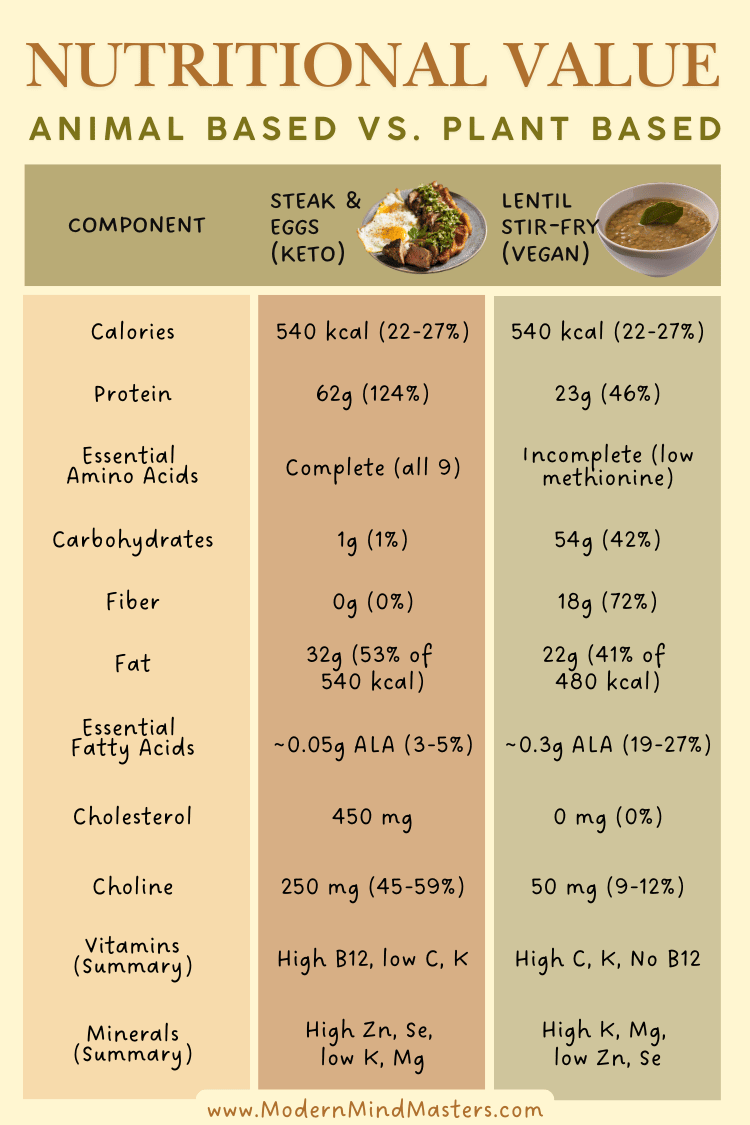

Ketogenic-type diets, including stricter forms such as the increasingly popular carnivore diet, are the largest advocates for not consuming any (or very few) carbohydrates.

While this may seem extreme at first glance, once we understand that carbohydrates are non-essential, serve no health purpose that the body can’t produce itself, and lead to damaging glucose spikes that contribute to insulin resistance, it’s no wonder so many are choosing to forgo carbohydrates altogether.

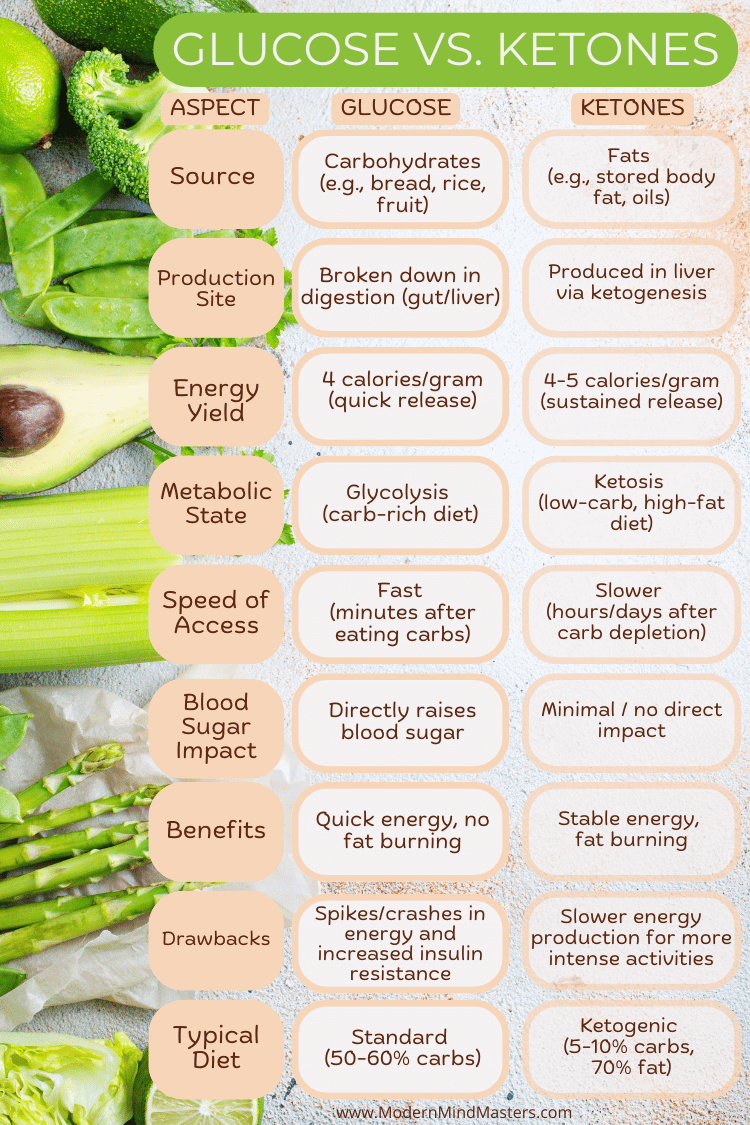

But what about glucose, the primary fuel source for several vital functions, especially for the brain and muscles during physical activity? Glucose is indeed essential for these activities, but the body can produce as much as it needs without consuming a single molecule of carbohydrates.

This process is known as gluconeogenesis which takes place primarily in the liver, where amino acids (from the breakdown of proteins), glycerol (from the breakdown of fats), and lactate (from anaerobic muscle activity) convert into glucose.

When glucose levels run below their maintenance threshold, the body enters ketosis, a state in which the liver produces ketones (a byproduct of fat breakdown) from fatty acids. While ketones don’t replace glucose for all functions, they serve as an alternative energy source, especially for the brain.

Those who oppose keto diets claim ketosis is a “back-up” function of the body, and that there are no long-term studies or data to show that it does not cause harm longer-term.

While the second part of this is true, there are no long-term studies that prove its safety (but also no studies that disprove it), I would argue that the opposite, of a long-term carb-based diet, has been shown to cause immense harm. Diseases and conditions related to insulin resistance have risen significantly in the last 100 years, in line with a massive increase in carbohydrate-type foods.

Humans appear to have evolved to thrive on a diet predominantly based on animal foods, relying primarily on fat and protein for energy. Early humans were hunter-gatherers, and while they did forage for fruits, vegetables, nuts, and roots, these carbohydrate sources were seasonal, scarce, and typically lower in calories compared to modern cultivated varieties. With large game providing substantial nutrition, animal products likely made up the majority of their caloric intake.

Given the limited availability of carbs, early humans would have naturally spent most of their time in a state of ketosis, where the body burns fat for fuel and produces ketones. The human digestive system, with its highly acidic stomach pH and lack of fiber-digesting enzymes, aligns more closely with carnivorous animals than herbivores. This suggests an evolutionary adaptation to a diet rich in animal fats and proteins rather than carbohydrate-based foods.

While modern diets often promote carbohydrates as a primary energy source, ancestral evidence suggests that our metabolic systems were built to efficiently use fat and ketones as fuel.

The ability to switch between glucose and ketones provided a flexible and resilient metabolism, supporting survival during periods of food scarcity and reinforcing the idea that carbohydrates were likely a supplementary, not primary, part of the early human diet.

This means that fiber should not be the first port of call for treating glucose and insulin spikes. Instead, we should live more in line with our natural tendencies by avoiding carbohydrate-heavy foods and diets as a frequent and dominant source of energy. Instead, we should train our bodies to run predominantly on ketones, to which most of our bodily processes are naturally attuned.

So long as your diet is not overly carbohydrate-heavy (for most, this will range from 50-100 grams of carbohydrates a day, depending on exercise levels), fiber will serve no purpose to lower blood sugar, as it will naturally be low. In fact, almost all sources of fiber come from carbohydrate-heavy foods (such as fruit and vegetables), creating a paradox.

That might not require to remove all of the carbohydrates from your diet. It might just mean you lower it to your personal tolerance level. Ketosis can be entered typically from less than 50 grams of carbohydrates a day, although this varies largely on individual metabolism, activity level, and genetics. Some, like my wife, need to be under 20 grams to maintain ketosis and suffer when above this. For me, however, 50 grams seems to be my limit.

The idea that fiber scrubs the colon clean, removing toxins that could otherwise wreak havoc, has been a staple of wellness advice for years. However, there’s a glaring problem: no evidence supports this claim. Nor is there a clear mechanism by which fiber could perform such a task.

The human colon is a dynamic, self-regulating system designed to keep itself in check. The epithelial lining of the intestines, for instance, is constantly renewing itself, shedding old cells and generating new ones in a process that naturally prevents the buildup of anything harmful.

Add to that the colon’s mucosal barrier—a slick layer of mucus that traps unwanted particles and ushers them out through regular bowel movements—and it’s clear the body has its own housekeeping well under control.

Beyond the colon’s self-cleaning capabilities, the broader detoxification narrative around fiber also falls apart under scrutiny. The notion that fecal matter lingers in the colon, releasing toxins that are then reabsorbed into the bloodstream, sounds alarming but lacks scientific backing.

In reality, the liver and kidneys are the body’s true detox powerhouses, tirelessly filtering and eliminating waste from the blood. These organs ensure that toxins don’t accumulate to dangerous levels, rendering the idea of fiber as a necessary detox agent more myth than fact.

Instead of fixating on fiber as a colon-scrubbing savior, we’d do better to appreciate the body’s innate ability to maintain its own balance, with a little help from hydration and a balanced diet that doesn’t consistently block them up.

Another top fiber myth is that fiber is essential for digestion, despite itself being indigestible by humans. While it is true that bacteria from soluble fiber can ferment to a certain extent in the lower part of the intestine, we can’t make use of the sugars that it releases.

Many assert that fiber is essential as a prebiotic, producing butyrate—a breakdown product—to nourish our cells. However, ketones derived from animal fats, namely beta-hydroxybutyrate, fulfill this role with greater efficiency and efficacy, bypassing the cumbersome mass of fibrous fruits and vegetables. In a state of ketosis, these butyrate-like benefits are directly supplied by ketones, diminishing the necessity for fiber-dependent short-chain fatty acid production.

So far we’ve learned that the body does not need fiber to perform its essential functions that allow the body and brain to survive. But what about those wishing to thrive? Are there disadvantages to fiber that suggest it is not only non-essential but potentially harmful?

Since fiber, especially insoluble fiber, can irritate the gut lining and create bulk that the body struggles to manage, many people experience bloating, gas, constipation, or diarrhea when consuming high-fiber diets. I only noticed these effects (namely bloating and gas) when I stopped eating fiber, however. Passing gas decreased almost completely, while my bowel movements reduced to once a day, every morning, without fail.

Studies have also shown that reducing or eliminating fiber can significantly improve symptoms of constipation and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). A study published in the World Journal of Gastroenterology found that patients with chronic constipation who eliminated fiber had more regular bowel movements than those on a high-fiber diet.

This study found that stopping or reducing dietary fiber significantly improved constipation symptoms. Patients who eliminated fiber increased bowel movements from once every 3.75 days to once per day, while those who reduced fiber saw an increase from once every 4.19 days to once every 1.9 days. In contrast, those who continued a high-fiber diet had no change, averaging one bowel movement every 6.83 days. Bloating occurred in 0% of the no-fiber group, 31.3% of the reduced-fiber group, and 100% of the high-fiber group, with similar trends for straining.

Fiber can also bind to important minerals, reducing their absorption, which might hinder nutrient uptake in a low-carb diet that prioritizes nutrient density.

Additionally, insoluble fiber can act as a mechanical irritant to the gut lining, potentially causing inflammation and discomfort. A fiber-free diet may reduce gut stress, enhance nutrient absorption, and provide a simpler path to gut health without the complications associated with fiber.

So are there any contexts where fiber is beneficial? There is no single answer for this, as any benefits from fiber seem to be context-dependent.

For those who know and are humble enough to admit they are on a less-than-ideal diet, fiber may do way more benefit than harm in offsetting glucose spikes and insulin resistance. Even diets typically considered “healthy”, such as the Mediterranean diet, may benefit from fiber if it includes over 50 grams of carbohydrates.

Some studies and sources claim fiber can help with cholesterol management, minimize certain gut health issues, and even prevent colon cancer. However, these issues are so complex and dependent on so many factors that such parallels are difficult to prove.

I believe the only people who actually NEED carbs are those who are about to undertake a high-energy activity or engage frequently in moderate to intensive physical activity.

As a weightlifter who lifts heavy four times a week, I noticed I was running low on energy in my more intensive exercises. While I felt great on a keto diet (no pains or aches and my bloodwork was near perfect), I struggled a little more in the gym than I did before my keto diet.

I suspect that the body’s ability to produce its own glucose and ketones for energy is limited by how fast it can be produced. The body was not made to deadlift and squat as heavily as possible four times a week. As a result, the bodycan struggle to keep up with such extreme activities.

In response, I have added a moderate amount of simple carbohydrates on days that I exercise, typically between 50 – 100 grams of potatoes and a piece of fruit. It seems to hit the right balance for me and my lifestyle. While I believe it may not be perfect for my bloodwork and ultimate longevity, the compromise seems to be relatively minor in the grand scheme, where lifting adds so much value to my happiness and quality of life.

This small amount of carbohydrates adds around 15g of fiber to my diet a day. While not necessary, it’s an unavoidable by-product of consuming carbohydrates and may help dampen the effects of glucose spikes. I believe the body can handle this small amount perfectly fine, even if it’s slightly less than ideal.

Although the science is still debated, and likely will be for a while, it is clear that fiber isn’t as universally essential as we were once told. The problem is that this doesn’t mean that fiber isn’t still useful to some degree, but the circumstances are situational.

If you know you have a terrible diet, high in carbs and sugar and low in quality natural animal fats and proteins, fiber may help to offset some of the worst effects of glucose spikes. But this is like saying it’s best to wear body armor when crossing a warzone. The better option would be to not cross a war zone altogether, by avoiding carb and sugar-high foods that warrant mitigating actions.

Fiber and carbohydrates are closely related – generally, the more carbohydrates you consume, the more fiber you will need to offset glucose and insulin-raising spikes.

If you are very physically active, carbohydrates may be beneficial to ensure your energy levels can keep up with the physical demands on your body and brain. Only a moderate amount of less than 100 grams a day is needed, and hence only a small amount of accompanying fiber.

Fiber is not essential. Unlike other essential elements like vitamins and minerals, fiber is not required for basic survival.

While these indigestible molecules will certainly add bulk to stools, I can attest, however, that fiber is not necessary for regular and effective movements. As someone who switched to a diet with zero fiber or carbs for over a year, I’ve had perfectly regular bowel movements without any issues.

This is the only real strong argument for including fiber in your diet – to reduce insulin spikes from glucose. But where is the glucose coming from? If we look one layer deeper, we soon see that consuming fiber to control your insulin spikes is a little like putting a Band-Aid on a leaking pipe.

Similar to how it is better to replace the pipe than keep patching it up, it is better to not consume glucose-spiking foods that require fiber to mitigate.

The 5 best evidence-based supplements for anxiety include passionflower, kava, St John’s wort, L-arginine, and magnesium, according to recent research.

Rejection sensitivity, and its unofficial diagnosis RSD, is thought to be related to ADHD, often mistaken as a symptom. But rejection sensitivity can be treated.

Logical and rational thoughts stem from the conscious mind, whereas emotional and impulsive thoughts are induced from the subconscious mind, which is beyond our control.

Twitter Instagram Pinterest Key Points: Recent studies challenge long-held beliefs about tap water safety, questioning

Humans are unpredictable by nature, so boosting our social skills is one of the strongest weapons we can use for successful communications. Here are 3 of the best books on social skills.

Learn how exercise helps the brain, from reduced inflammation, slowed brain aging, and improved cognitive performance.

© 2025 Modern Mind Masters - All Rights Reserved

You’ll Learn:

Effective Immediately: 5 Powerful Changes Now, To Improve Your Life Tomorrow.

Click the purple button and we’ll email you your free copy.