Water Fasting – The Benefits, How Long To Fast, And How To Fast Safely

Water fasting is becoming an increasingly popular therapeutic treatment for a range of illnesses and diseases. Learn how to make a water fast work for you.

Do you find yourself hitting the snooze button more often than you’d like, or perhaps spending more time in bed than awake, wondering how to stop oversleeping? Oversleeping might seem like a luxury to some, but it can be a sign of deeper issues affecting your sleep quality and overall health.

Contrary to popular thought, a healthy person cannot and will not sleep more than their biological needs. So when we talk about oversleeping, what we really mean is that we’re not getting the good, deep sleep we need to feel fully rested during a reasonable time frame.

Thus, for most, oversleeping stems from lacking sufficient sleep quality and efficiency and making up for this by sleeping longer, which often results in oversleeping.

In this article, we’ll explore the hidden impacts of oversleeping and introduce actionable steps you can implement today to prevent it. From understanding the science of sleep cycles to identifying the lifestyle habits that contribute to excessive sleep, we’ll arm you with practical strategies and actionable tips to break free from the chains of oversleeping.

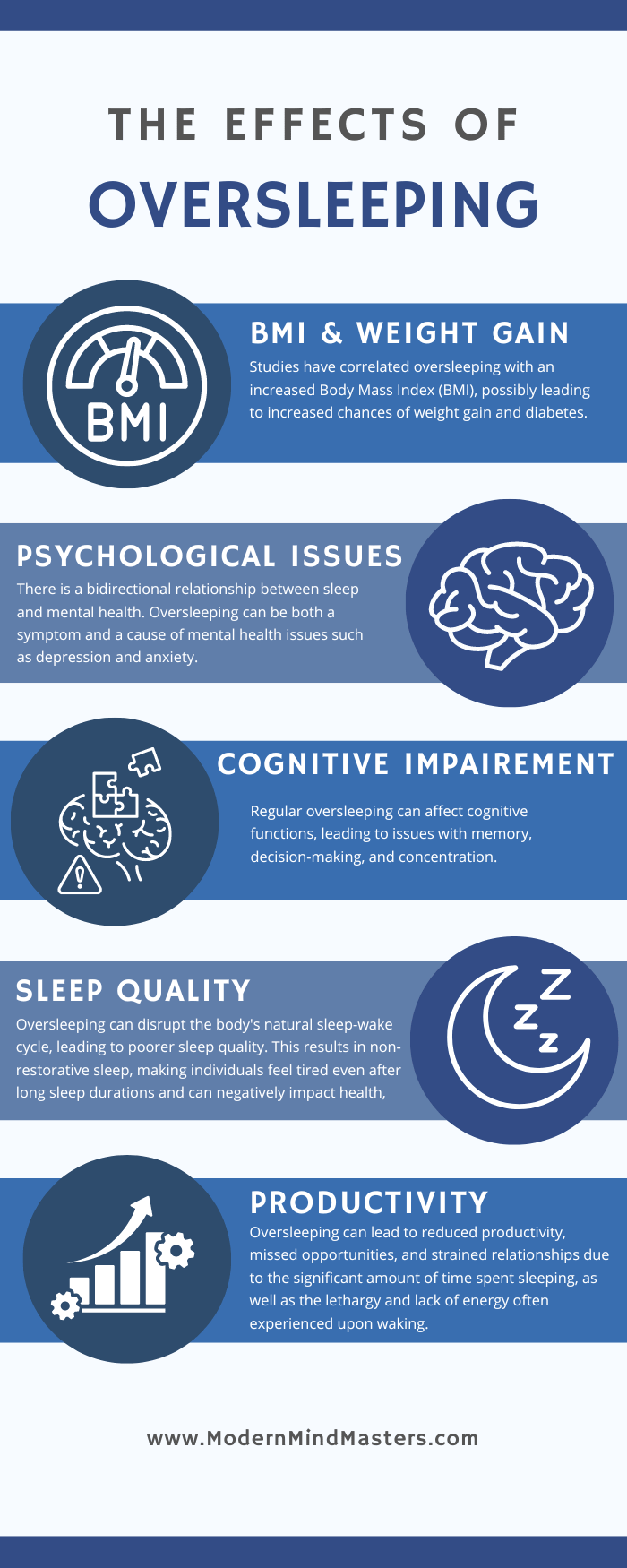

While we often hear about the dangers of getting too little sleep, the risks associated with oversleeping are less frequently discussed, yet equally concerning.

Research has uncovered a U-shaped association between sleep duration and various health risks, indicating that both insufficient sleep and excessive sleep can lead to health problems.

In particular, those who sleep for extended periods, known as “long sleepers,” are more likely to encounter psychiatric disorders and have a higher body mass index (BMI), pointing towards an increased risk of obesity.

While specific physiological pathways and risks of oversleeping are still being explored, the evidence strongly suggests that consistently sleeping more than the recommended 7-9 hours for adults can lead to adverse health outcomes.

As with anything in life, finding a balance in your sleep schedule is crucial. Adequate sleep supports your health, but too much of it may inadvertently lead to complications that affect your mental and physical well-being.

Your sleep schedule, encompassing both when you drift off at night and when you awaken, should orbit around a specific duration of restful sleep. While conventional wisdom recommends targeting 8 hours of sleep per night, a wealth of research suggests that the sweet spot for optimal daytime functioning falls between 7 to 7.5 hours of high-quality sleep.

Unfortunately, this number is highly variable and dependent on many factors. Sleep duration is typically inversely proportional to age: Young children between 3 and 5 need between 10 and 14 hours of sleep, while adults require between 7 and 9 hours.

For you individually, however, other factors such as genetics, exercise, stress levels, diet, BMI, and amount of deep rapid-eye movement (REM) sleep all determine the minimum period of sleep required. As there is no way to calculate this optimum directly, you must gauge this amount through trial and error.

We all struggle to wake up first thing; even after an excellent night’s sleep we require at least 30 minutes to really get going. If you are still struggling an hour or so after waking, or feel excessively tired during the day, it’s a strong indication that you require more sleep.

Note, however, that time spent in bed with your eyes closed does not equate to sleep. Sleep quality is just as important as quantity, another factor that needs consideration. Although the studies recommend 7 hours or more, 8 is usually suggested to make up for the fact that there might be a delay between when we settle down to sleep and when we begin to sleep.

Use an 8-hour sleep window as a starting point, and after a few consistent weeks, gauge how tired you feel an hour after waking and throughout the day. If you find yourself crashing in the late afternoon or early evening, that too is another strong indication that you may require more sleep.

So now you know why sleeping is bad for you, how to find your optimum sleep duration, and that stopping oversleeping requires trial and error and consistent practice for at least a few weeks.

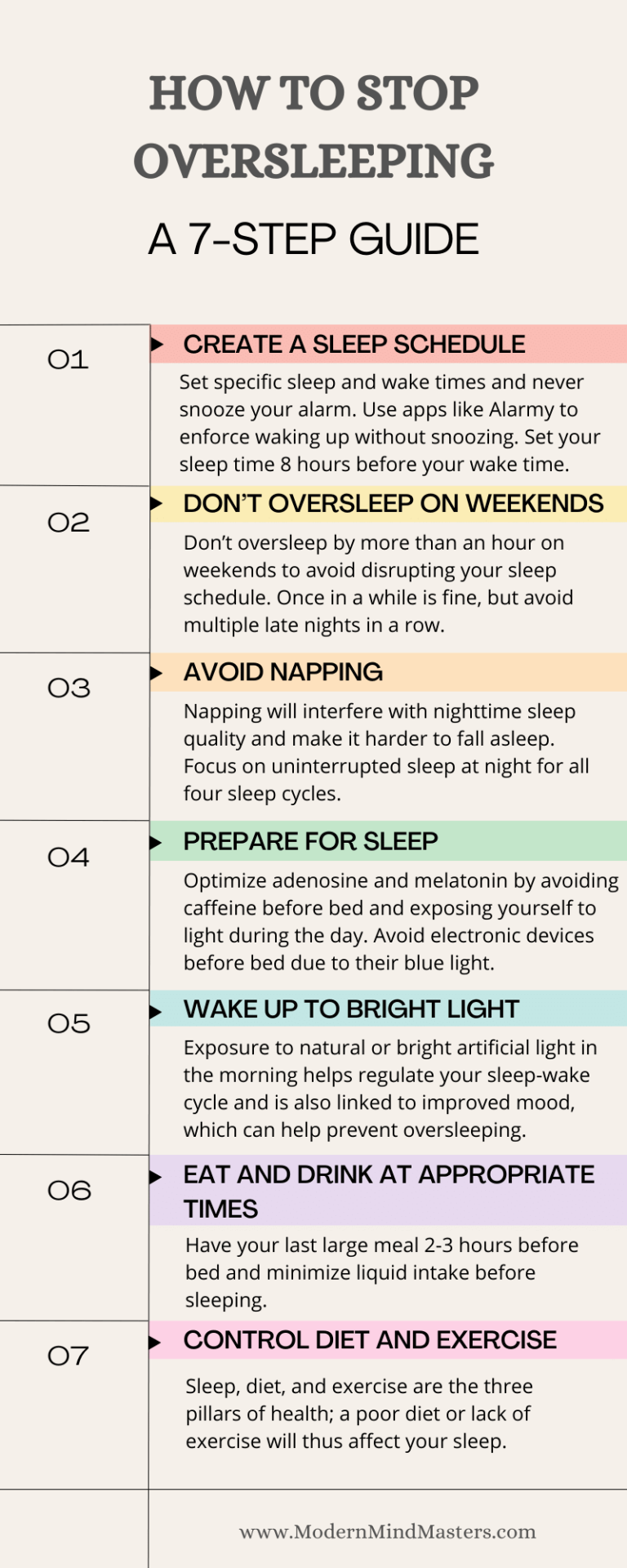

With that in mind, you are now ready to follow these seven steps and begin your transition to creating a healthy and productive sleep routine, without oversleeping.

If you only take one thing from this article, let it be this: You must set your sleep and wake times in stone. Like all SMART goals, be very specific. Whether your sleep time is 9 pm, 9:45 pm, or 11:32 pm, take this number to heart and stick to it, whether tired or not.

The time you wake up is often dictated by your work schedule. But once again, set this in stone. Set your alarm for whatever time you need to every morning, and NEVER SNOOZE. If you work from home or have flexibility when waking, you still need to pick a time and stick to it religiously. Again, NEVER SNOOZE!

Although it may seem obvious, sticking to a set wake-up time (and did I mention not snoozing?) is essential to crafting a robust habit and sleep schedule.

Third-party apps like Alarmy won’t stop the alarm until you take some steps, such as solving a puzzle or taking a photo of something specific. It’s a free app on both iOS and Android, so there’s no harm in trying, and it may just be what you need to break that snooze habit.

Setting a sleep time, however, is often more difficult, as we would all love to watch just one more episode of “The Office” before sleeping. With careers and family life, sometimes the only time we truly get to relax is late at night once everything else is done.

You’ll have to make an extra effort to stick to your dedicated sleep time. I suggest starting it 8 hours before your wake time and adjusting as you feel necessary after a few weeks of routine.

While creating a sleep schedule is the most fundamental step in preventing oversleeping, it can also be the most difficult to implement. Expect a few nights of struggling to fall asleep and/or waking up, depending on your previous sleep habits.

Be sure to stick with it for at least a couple of weeks; as each night passes and your body adjusts to its new schedule, you will find it easier to fall asleep, and the consistency should increase your sleep quality.

One of the most common causes of oversleeping is on the weekends when you have the time to oversleep. While understandable (after a hard week’s work, we all want a little extra rest time), the benefits gained from a few extra hours in bed are usually offset by the disruption to sleep schedule and quality.

While I recommend waking up at the same time during the weekend that you do in the day, that is, waking up at the same time every single day of the week, I understand this is not practical in the real world, especially for those of you lucky enough to have social lives.

It will be fine to delay your wake time by 1 hour without affecting your ability to fall asleep later. For example, I wake at 5 am every day during the week but will wake at 6 am on the weekend if I stay awake longer on a Friday or Saturday night.

Once in a while, say once every few weeks, it’s also fine to break this rule completely, such as a one-time event. When seeing Ed Sheeran in Vancouver, for example, I didn’t sleep until 2 am. While I felt a little groggy the next day, it did not affect my ability to fall asleep the next night, and so did not negatively impact my sleep schedule.

When I worked a night shift for three nights in a row, however, it wrecked my ability to sleep for a few days afterward. Thankfully, my sleep schedule was routine enough to recover quickly, but breaking your sleep routine for more than a day or two is a slippery slope to ruining your ability to fall asleep and your sleep efficiency.

While admittedly extremely pleasurable, napping will kill both your sleep quality and your ability to fall asleep.

Sleeping and napping are sometimes classified as core and optional sleep in scientific literature, and the two have been found to not be equal. Uninterrupted and quality sleep during the core period (typically at night) goes through all four sleep cycles (3 NREM stages and 1 REM stage), all of which are equally important for restoration. Optional sleep, such as from napping, usually does not go through all four cycles.

This study looked at how people slept when given extra time by either a single 14-hour period at night or 16 hours divided between 12 hours at night and 4 hours during the day.

In the beginning, people slept more, showing they were catching up on missed sleep. This increase in sleep happened for the first 1-3 days and included more deep sleep and longer sleep times, with people falling asleep faster.

However, after a few days, people started to sleep less, and it took them longer to fall asleep, indicating their bodies were adjusting back to a normal sleep pattern after catching up on sleep. The findings suggest that our bodies naturally regulate sleep to make up for lost rest but then return to a regular sleeping pattern. Again, the body is very good at regulating sleep, and a healthy person will not be able to sleep past their biological needs.

In the study, those who did not nap fell asleep faster than those who did, possibly because they had been awake longer before trying to sleep (10 hours vs. 4 hours). In both groups, it took longer for participants to fall asleep over the first few tries.

This could be because their need for sleep decreased as they caught up on rest and because their bodies started producing the sleep hormone melatonin later in the night due to the adjusted sleep schedules.

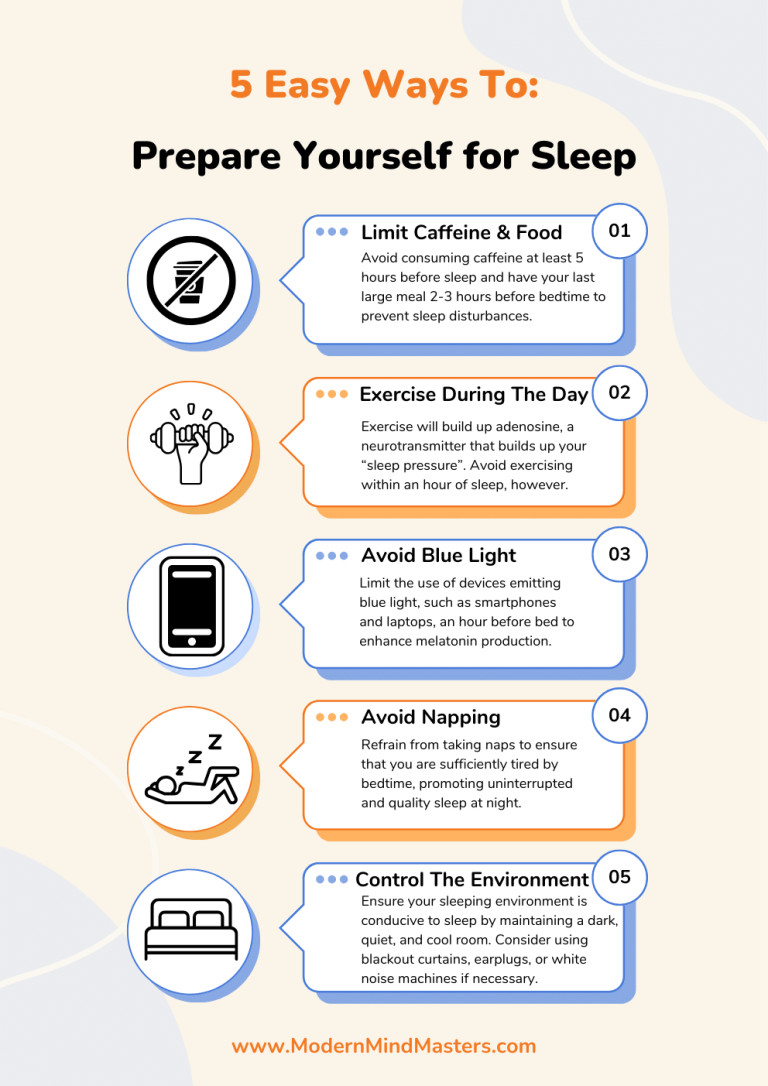

You need to prepare yourself and your environment for a good night’s sleep.

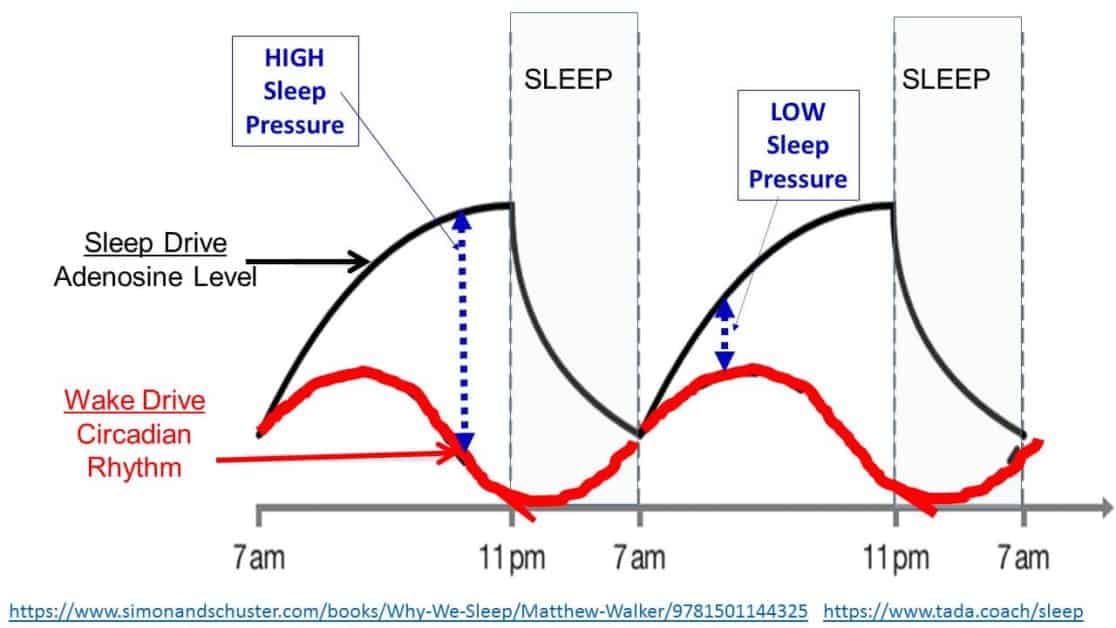

The most active way we can do this is to optimize adenosine and melatonin, the two critical players in the complex game of sleep regulation.

Adenosine is a neurotransmitter that accumulates in our brain throughout the day, gradually increasing and building our desire to sleep.

You can think of adenosine as a sleep pressure gauge; the longer we’re awake, the higher the pressure builds and the sleepier we become. This process is naturally regulated by the body’s internal clock, leading us towards a state of readiness for sleep as night falls.

Melatonin is a hormone that signals to our body that it’s time to sleep and is produced in response to darkness, helping regulate our sleep-wake cycle by encouraging feelings of sleepiness and lowering body temperature.

Adenosine and Melatonin are inversely related. We want adenosine levels low, and melatonin high when we are about to sleep.

Caffeine blocks adenosine receptors, which is great for helping us feel alert, but not so great for sleep. Caffeine has a half-life of around 5 hours, meaning half the caffeine you consume is still in your blood 5 hours after consuming, so you should avoid caffeine-containing beverages and foods at least 5 hours before sleep.

Exercise, on the other hand, helps to naturally build up adenosine levels through energy expenditure, although it is not recommended to exercise immediately before bed.

To enhance melatonin production for improved sleep, try to expose yourself to natural light during the day and maintain a dark environment at night to support your body’s natural melatonin production based on natural circadian rhythms.

Don’t use electronic devices right before bed, as the blue light emitted can suppress melatonin levels and disrupt your sleep cycle. A study shared by Harvard Medical School exposed the negative effects of blue light technology on sleep, highlighting its effect on melatonin production. This included TVs, phones, and any other light-emitting technology.

Light plays a crucial role in regulating the body’s natural sleep-wake cycle by influencing the body’s master clock in the brain. Exposure to natural daylight has been shown to shift sleep to earlier times, affecting how long we sleep and its quality.

Outdoor activity, which often coincides with light exposure, is also thought to contribute to these effects, though the exact impact of light versus physical activity is still being explored.

The earlier you receive light on your skin and retinas, the better, as it signals to your body that it’s time to be awake. Unfortunately, many of us wake up hours before sunrise, so bright artificial lights are the next best thing.

Do not sit in bed trying to stay awake in the dark. Chances are you’ll struggle to wake up and likely fall back to sleep and oversleep.

Light has also been shown to have a positive impact on mood, especially through the serotonin-producing cells found in the skin. It is easier to not oversleep when we have an improved mood; depression and anxiety have been linked with oversleeping.

Contrary to common belief, there is a natural cap to how much sleep our bodies can indulge in, governed by other bodily needs like hunger or the call of nature, highlighting the importance of striking a healthy equilibrium between our daily routines and physiological demands (like timely meals and hydration).

Eating heavy meals or spicy foods close to bedtime can lead to discomfort, indigestion, or heartburn, making it harder to fall asleep or stay asleep. Additionally, late meals will cause digestion when you are trying to sleep, an energy-intensive process that can disrupt and delay the natural sleep cycle, leading to oversleeping.

Aim to have your last large meal at least 2-3 hours before bed to allow digestion to occur and minimize sleep disruptions. Some health professionals have advocated for intermittent fasting, a dietary pattern that cycles between periods of eating and fasting, to improve sleep, although there is no clear-cut data to confirm this.

Consuming foods high in tryptophan, carbohydrates, or certain fats may increase serotonin levels which are converted into melatonin, the sleep hormone. While melatonin is productive for sleep, it is timing-dependent – eating these foods too close to bedtime can disrupt its timing.

Eating sugary foods or refined carbs before bed can spike blood sugar levels, leading to energy bursts that can keep you awake. Later, as blood sugar drops, you might wake up feeling hungry or unsettled. While I recommend avoiding all foods for 3 hours before sleep, especially avoid sugary ones.

Alcohol and caffeine consumed late in the day should also be avoided – they can stimulate your nervous system and block adenosine, preventing your brain from naturally relaxing at night.

Similarly, while alcohol might initially act as a sedative, it can severely affect sleep quality and architecture when consumed in larger amounts, leading to disruptions in sleep cycles and decreased restorative sleep.

Proper hydration is essential for good sleep, but timing matters. Drinking too much liquid before bed can lead to frequent awakenings to use the bathroom, disturbing your sleep cycle. Ensure you drink enough to remain hydrated throughout the day and reduce water intake when approaching sleep.

Sleep, diet, and exercise are the three pillars of health, operating in synergy to keep your body and brain operating at peak health and efficiency. A disruption in any of these can lead to serious effects in both others, meaning that to sleep well, we need to control our diet and exercise.

The body doesn’t oversleep for no reason; you may have been in bed for 14 hours, but that doesn’t mean you achieved 8 hours of solid restorative sleep.

We can reduce the amount of hours slept by increasing the quality of sleep, and we can do this through improving the other two tenets of health: diet and exercise.

Exercise has been shown through hundreds of studies to improve sleep; a review of studies published between 2013 and 2017, which adhered to the American College of Sports Medicine’s exercise guidelines, found that, out of 34 studies that met the inclusion criteria, 29 reported that exercise improved sleep quality or duration.

The impact of diet on overall health is so significant that it has led to the emergence of a specialized field known as nutritional psychiatry, an area of study that focuses on the microbiota-gut-brain axis as the key nutrient-based system crucial for sleep regulation. Essentially, the foods we consume have a major influence on our sleep quality, which in turn affects our tendency to oversleep.

There’s evidence to suggest that a diet rich in dietary fiber can help mitigate or prevent inflammation, thereby enhancing both sleep quality and mental health. A comprehensive meta-analysis has revealed that diets high in fruits, vegetables, fish, and whole grains (commonly known as a Mediterranean Diet) correlate with a lower risk of depression and sleep disorders.

Similar research also indicates a negative relationship between consuming meat, including processed and unprocessed red meat, and the quality and duration of sleep. This may be due to lower levels of tryptophan and tyrosine, amino acids that are precursors to serotonin and melatonin, which are vital for mood regulation, sleep, and cognitive functioning.

The synergy between diet and exercise plays a pivotal role in combating oversleeping, as both elements profoundly influence sleep quality. By optimizing our sleep through these avenues, we can achieve a state of deep rest more effectively, thereby reducing the likelihood of oversleeping.

If, even after improving your sleep schedule and putting the above steps into practice, you still suffer from extreme daytime sleepiness despite getting sleep that should be adequate, known medically as hypersomnia, you may be suffering from a medical condition that needs qualified and professional assistance.

Depression can lead to changes in sleep patterns, including both insomnia (difficulty sleeping) and hypersomnia (oversleeping). Conversely, irregular sleep patterns, such as oversleeping, can exacerbate symptoms of depression. This cycle can create a feedback loop where depression leads to oversleeping, which in turn, worsens depression.

Depression is associated with imbalances in neurotransmitters and hormones that regulate mood and sleep, such as serotonin, melatonin, and GABA. These imbalances can disrupt the sleep-wake cycle, leading to oversleeping.

Sleep disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea can also cause oversleeping due to breathing interruptions that lead to fragmented, poor-quality sleep, causing individuals to oversleep to try to compensate.

Thyroid issues, Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS), Medications, Substance Abuse, and Neurological Conditions can all lead to oversleeping as a symptom and must be discussed with a medical professional.

Navigating the challenge of oversleeping goes far beyond the simplicity of alarm clocks, venturing into the complex realm of lifestyle adjustments tailored to your body’s intrinsic needs.

Crafting a consistent and healthy sleep schedule is key to developing a beneficial sleep pattern, ensuring that your sleep is of high quality, reducing the time you need to spend in bed, and cutting down on the urge to oversleep.

The journey to avoid oversleeping demands perseverance and consistency to build a strong sleep habit that will stick with you. This 7-step guide not only serves as a blueprint for cultivating a productive sleep routine but also emphasizes the importance of addressing the underlying factors that contribute to oversleeping, such as diet, exercise, and screen time before bed.

Remember, the path to improving your sleep pattern is a personal one, requiring you to listen to your body’s signals and make adjustments as needed. Learning how to stop oversleeping is part of this journey. As you embark on this path, keep in mind that the benefits of a well-regulated sleep schedule extend far beyond the morning alarm, offering profound impacts on your overall health, mood, and quality of life.

Those who sleep for extended periods, known as “long sleepers,” are more likely to encounter psychiatric disorders and have a higher body mass index (BMI), pointing towards an increased risk of obesity.

For most, oversleeping stems from lacking sufficient sleep quality and efficiency and making up for this by sleeping longer, which often results in oversleeping.

You must set your sleep and wake times in stone. Like all SMART goals, be very specific. Whether your sleep time is 9 pm, 9:45 pm, or 11:32 pm, take this number to heart and stick to it, whether tired or not.

Water fasting is becoming an increasingly popular therapeutic treatment for a range of illnesses and diseases. Learn how to make a water fast work for you.

Analysis paralysis occurs when overanalyzing a situation results in a lack of ability to make a decision. These effects are worsened in those with ADHD, leading to ADHD paralysis.

Follow these 7 simple steps that work alongside your body to learn how to stop oversleeping.

Unlocking the power of a smile is as much of a science as it is an art. From increasing dopamine and serotonin to greatly improving your career success, a simple smile can improve your life significantly.

Mindfulness, the state of being aware of something, is the fundamental trait of awareness and self-improvement. Learn how to master this lost art.

Autosuggestion can help you unlock the power of your subconscious mind in the same way a placebo can result in physical healing.

© 2025 Modern Mind Masters - All Rights Reserved

You’ll Learn:

Effective Immediately: 5 Powerful Changes Now, To Improve Your Life Tomorrow.

Click the purple button and we’ll email you your free copy.