The Failure Paradox – How Failure Is Fundamental To Success

Learning from failure is nature’s most efficient learning mechanism, yet as adults, we try to avoid failure at all costs. Instead, we should learn how to fail the correct way.

Let’s set the record straight right away: meat is good for you. Period.

Not only is meat good for you — it may well be the single best food humans can eat.

Hippocrates, often called the “Father of Medicine,” once said:

“Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food.”

If we think of food as medicine, then meat is the most powerful prescription nature ever wrote.

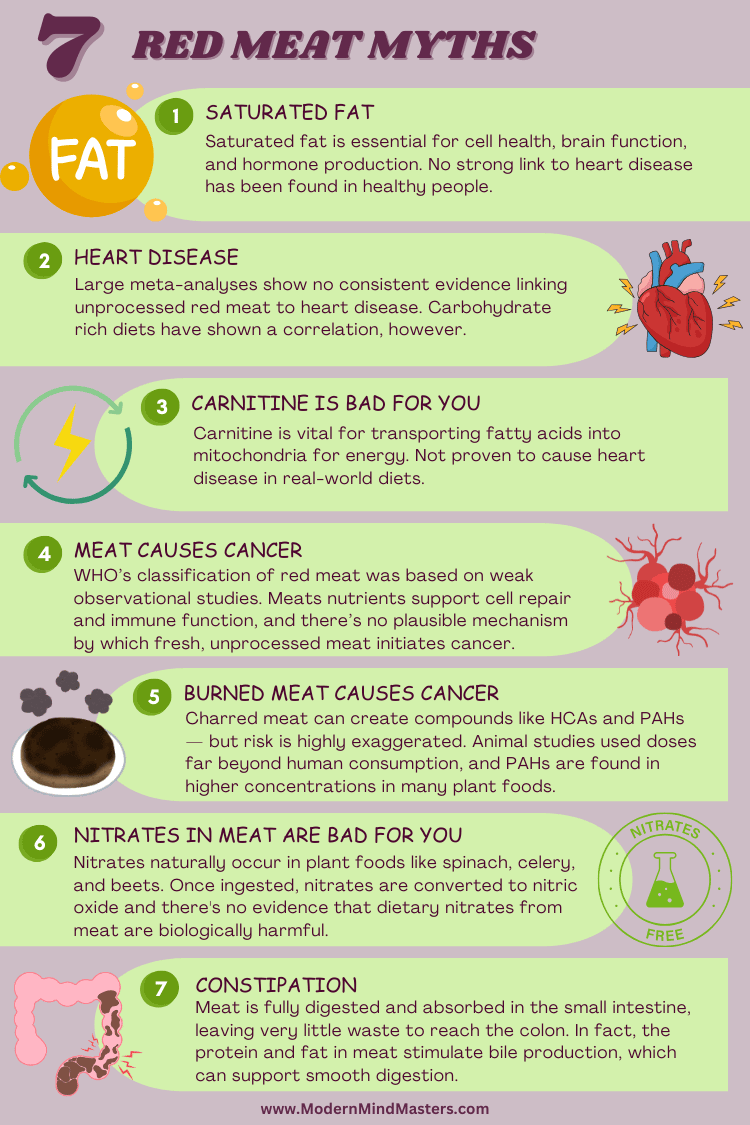

I can feel many of you already in disbelief, so this article is dedicated to debunking the most common mainstream myths surrounding meat — from its saturated fat content (yes, saturated fat is not the villain you’ve been led to believe) to its supposed cancer-inducing effects (which are simply false).

While it would be nice to attribute these myths to the limits of epidemiological studies, the truth is, there’s a lot of foul play involved — including heavy industry influence, like The Seventh-Day Adventists funding a significant portion of plant-based studies to fit their religious narrative.

We’ll cover the most common meat myths and use newer studies, biology, and common sense to debunk them thoroughly. If you’re not currently including good-quality meat in your diet, this may be one of the most important articles for your general health you’ll ever read.

Let’s start with the most common myth: that the saturated fat from meat, especially red meat, is bad for you.

Over the past ten years, the narrative has been that saturated fat raises cholesterol, clogs arteries, and triggers heart attacks. Wrong, wrong, and wrong again.

This myth can be traced back to the 1950s when American physiologist Ancel Keys proposed the Diet-Heart Hypothesis — the idea that saturated fat raises cholesterol, and high cholesterol causes heart disease.

To support his theory, he published the now-famous Seven Countries Study, which showed a strong correlation between saturated fat intake and heart disease rates across several countries.

But here’s the catch: he cherry-picked the countries. Out of the available data from 22 countries, Keys only included the 7 that best fit his hypothesis and left out those that didn’t — like France, where people ate lots of saturated fat but had low rates of heart disease (now known as the “French Paradox”).

Unfortunately, this flawed study heavily influenced the U.S. Dietary Guidelines (1980), demonizing saturated fat and promoting a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet — which paved the way for the processed food boom and, ironically, likely contributed to the rise in obesity, diabetes, and metabolic disease.

So how do we know this is wrong? First, let’s look at some studies.

In 2020, the Journal of the American College of Cardiology published a major review on saturated fat and health, concluding there’s no convincing evidence that cutting saturated fat lowers the risk of heart disease or extends lifespan.

The following year, an international panel of experts — including two former members of the U.S. Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee — reached the same verdict. After combing through the research, they found no solid scientific reason to limit saturated fat to 10% of daily calories — a policy that has shaped American nutrition guidelines for decades.

It’s easy to get lost in studies, which — especially in the multi-faceted world of nutrition — can be speculative and unreliable for real-world use. So let’s take a look at some biology.

Human Evolution:

For most of human history, saturated fat was a staple of the diet. Hunter-gatherer societies prized fatty animal meat, organs, and marrow — all rich in saturated fat — as dense, reliable sources of energy and fat-soluble nutrients (like vitamins A, D, E, and K). Our biology evolved to efficiently digest, metabolize, and thrive on these fats.

Cellular Structure:

Saturated fat isn’t some foreign invader — it’s part of you. Every cell membrane in your body is made from a mix of saturated and unsaturated fats. Saturated fats help provide stability and structure to these membranes. Your body also uses saturated fat to make hormones and support immune function.

Breast Milk:

One of the most striking biological clues: human breast milk contains a significant amount of saturated fat — because growing babies need it for energy, brain development, and building new cells.

Cholesterol Misunderstanding:

The “saturated fat = heart disease” theory was largely based on early studies that observed a rise in blood cholesterol when people ate more saturated fat. But the problem is, total cholesterol isn’t a reliable predictor of heart disease. Your body tightly regulates cholesterol levels, and the type and size of cholesterol particles matter much more than the total number — something early studies didn’t account for.

Yet, despite the saturated fat theory crumbling under modern research and basic biological common sense, the idea that red meat causes heart disease still lingers. With saturated fat off the hook, some researchers have shifted their focus to a new suspect: carnitine, another naturally occurring compound in red meat.

Since we now know saturated fat from meat isn’t the nutritional enemy we were led to believe, does red meat have any link to heart disease in general?

The links between red meat and heart disease are based on two bodies of research: nutritional epidemiology studies seeking associations between red meat consumption and heart disease risk, and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) exploring how red meat affects blood levels of LDL “bad cholesterol” and/or triglycerides.

We know nutritional epidemiological studies are often unreliable, simply because they rely on self-reported food questionnaires — which are notoriously inaccurate — and by design, these studies can only show correlation, not causation.

On top of that, human nutrition is incredibly complex and multifaceted, making it nearly impossible to isolate a single food or nutrient and fairly conclude that “X leads to Y.”

There are simply too many variables at play: genetics, lifestyle, environment, stress, sleep, exercise, and countless other dietary factors all influence health outcomes, yet are often overlooked or unmeasured. This is why so many nutrition headlines sound contradictory, and why long-held beliefs — like the fear of saturated fat — deserve to be questioned.

If you’re looking for studies to prove that red meat does not lead to heart disease, the gold standard is meta-analysis.

A single observational study can only suggest a possible link, but a meta-analysis pools data from multiple high-quality studies, which helps cancel out random anomalies, weak associations, and bias. When well-conducted, meta-analyses offer the most reliable summary of the current evidence.

In 2020, researchers from Cornell and Northwestern University analyzed data from six large-scale epidemiological studies involving nearly 30,000 participants. Their meta-analysis, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, aimed to explore the link between red meat consumption and heart disease.

What they found was surprisingly underwhelming. Adding just two extra four-ounce servings of unprocessed red meat per week was linked to only a 3% increase in cardiovascular risk. Statistically, this was reported as a “hazard ratio” of 1.03, which, in plain terms, means the risk barely budged.

For most respectable studies, a relative risk under 2.0 is considered too small to draw meaningful conclusions, and a hazard ratio of 1.0 would indicate no increase in risk. Essentially, this study did not find any meaningful hint of a connection.

When it comes to randomized controlled trials (RCTs) — the gold standard of scientific research — there has never been a human study specifically designed to test whether eating red meat causes or worsens heart disease. This is likely due to the significant logistical and ethical challenges such a study would pose.

Instead, researchers have focused on a different approach: numerous RCTs have examined whether red meat consumption raises LDL cholesterol and triglyceride levels, both markers historically linked to heart disease risk. However, even in this area, the evidence is inconsistent, with studies pointing in various, often weak, directions.

Despite these findings, many researchers still cling to the belief that a link between red meat and heart disease exists — even after saturated fat, the nutrient once blamed as the main culprit, has largely been cleared of guilt. The lack of clear evidence only underscores the complexity of understanding how diet truly influences heart health and highlights the need for a more nuanced approach to nutritional science.

One of the more recent attempts to pin heart disease on red meat focuses on carnitine — a vital nutrient found abundantly in beef. Carnitine’s main job is to shuttle fat into your cells’ mitochondria, where it’s burned for energy. In fact, it’s so essential that if you don’t get enough from food, your body will make it from scratch.

Red meat naturally contains more carnitine than white meat because red muscle fibers rely more heavily on fat for fuel, while plant foods are almost devoid of it — they simply don’t need much, since plants primarily burn carbohydrates for energy.

So where did the carnitine scare come from? A 2013 study from the Cleveland Clinic raised alarms when researchers claimed carnitine might increase the risk of heart disease. But when you look closely, the study falls apart:

Despite these shaky findings, the study has been cited thousands of times and continues to fuel the myth that red meat equals heart disease. As it stands today, the “carnitine → TMAO → heart disease” theory remains unproven — yet it’s still repeated as if it were fact.

In 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO) sparked global headlines with a bold claim: processed meat causes cancer, and red meat probably does too. The warning came from a short two-page report, yet it sent shockwaves through the health world — and for many people, the idea that steak or bacon might lead to cancer stuck.

But when you peel back the hype and look at the evidence, the story isn’t nearly as clear-cut.

The WHO based its conclusions mostly on epidemiological studies — the kind of research that can only observe patterns, not prove cause and effect. Out of over 800 studies, the WHO narrowed its focus to 56 human trials related to colorectal cancer. When you break that down, it becomes obvious how weak the case against red meat actually is:

The experimental data wasn’t any stronger. The WHO cited only six experimental studies — just two involving humans — and the rest were done on rats. In these rodent studies, the animals were literally injected with potent cancer-causing chemicals before being fed meat-based diets.

Even then, no rats developed cancer unless their diets were stripped of calcium — a critical nutrient that naturally protects the gut lining.

And in the human studies? The researchers used small groups and often flawed designs. Some volunteers were fed poorly packaged ham or forced onto strange, fiber-deficient diets paired with processed carbs, yet researchers still couldn’t produce reliable signs of cancer risk.

In short: the WHO’s claim rested on conflicting population data, cherry-picked lab studies, and experiments so convoluted they told us more about bad research design than about meat and cancer.

Even a panel of cancer experts from eight countries reviewed the data and summed it up perfectly:

“Epidemiological and mechanistic data on associations between red and processed meat intake and colorectal cancer are inconsistent and underlying mechanisms are unclear.”

Translation? Science hasn’t proven that eating meat causes cancer — not even close.

One of the most common arguments against eating meat is that cooking it — especially grilling, smoking, or charring — produces chemicals called PAHs (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons) and HCAs (heterocyclic amines), which have been shown to cause cancer in lab animals.

Sounds scary, right? But here’s the part that rarely makes the headlines: the amounts used in these animal experiments were 1,000 to 100,000 times higher than what you’d ever encounter in your actual food. Unless you’re planning to dine on piles of burnt meat every day, the risk is purely theoretical.

Even human studies haven’t been able to back up the fear. The only research available on this topic comes from the dreaded epidemiological studies — and these have been inconsistent and inconclusive at best.

It’s also worth noting that these compounds aren’t unique to meat. HCAs can form in any protein-rich food — including fish and poultry — whenever it’s exposed to high heat. PAHs show up in both plant and animal foods after smoking, toasting, or frying.

Surprisingly, some of the highest levels aren’t found in meat at all — but in everyday staples like flour, cereals, breads, and even cocoa products. In fact, bread and cereals can contain PAH levels more than a thousand times higher than what’s typically found in cooked meat.

Nitrates and nitrites are often used as preservatives in processed meats like bacon, salami, and ham — and over the years, they’ve been heavily criticized as potential cancer-causing ingredients. But the story is a lot more nuanced than it sounds.

For starters, nitrates and nitrites themselves haven’t been shown to cause cancer. The concern arises from the fact that, under certain conditions, they can react with protein fragments to form nitrosamines — compounds that have been linked to cancer in lab animals (at much higher doses than humans typically encounter).

What’s often left out of the conversation is that the largest source of nitrates in the average diet isn’t processed meat — it’s vegetables. Foods like spinach, celery, and beets naturally contain very high levels of nitrates. In fact, ounce for ounce, spinach contains over 80 times more nitrate than hot dogs do.

So if nitrates were truly the villain, then we’d all need to start avoiding our leafy greens, too — which nobody is suggesting. The truth is, nitrates and nitrites have been part of the human diet for a long time, and the real cancer risk (if any) comes down to specific combinations and cooking conditions, not the simple presence of these compounds in your food.

One of the more persistent myths out there is the idea that meat is “hard to digest” — but in reality, the opposite is true.

Meat is actually one of the easiest and most efficiently digested foods we can eat. Our stomach acid, digestive enzymes, and bile are perfectly designed to break meat down into its simplest components: amino acids from protein, and fatty acids from fat.

Our stomach acid is highly acidic — similar to carnivores — which helps break down animal protein and kill harmful bacteria. We also produce specialized enzymes and bile designed to fully digest meat into amino acids and fatty acids.

Compared to herbivores, our shorter intestinal tract suggests less reliance on fermenting plant matter and greater efficiency in absorbing nutrients from animal foods. Once broken down, these nutrients are easily absorbed into the bloodstream, leaving almost no waste behind.

You’ve likely witnessed this in action at some point in your life. Have you ever noticed undigested pieces of meat or fat in the toilet? Probably not. But what about plant foods — seeds, peas, or corn? You’ve likely seen those come through more than once.

That’s because plant foods are wrapped in tough fibers and plant compounds that our bodies struggle to fully break down — and that’s perfectly normal. Meanwhile, meat is so bioavailable and easy to digest that hardly anything makes it through the process unabsorbed.

For some eating more meat means eating less fiber from plant foods, which we have also been told is bad. But high-fiber diets don’t help with constipation or digestion, contrary to popular belief. In fact, in a healthy whole-food diet free from excessive carbohydrates, fiber is not necessary.

So despite the popular narrative, meat isn’t a burden on your digestive system — it’s a food your body is built to handle with remarkable efficiency.

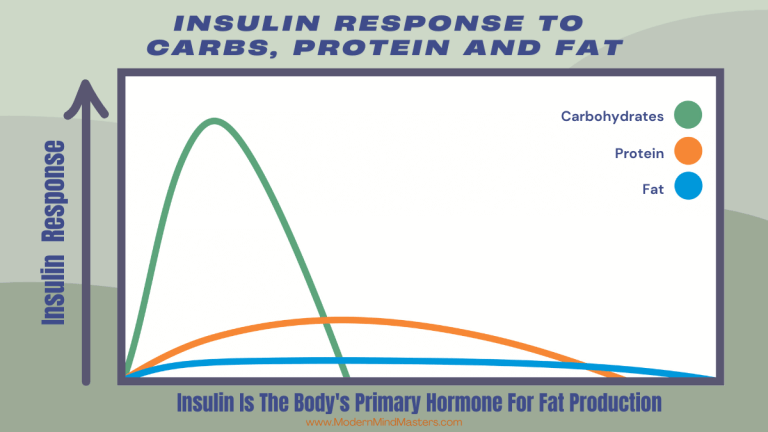

Obesity is a modern epidemic, and while it’s true that dietary habits play a significant role, meat is not the culprit. The key factor in weight gain is insulin — a hormone that regulates fat storage. Insulin levels spike when we consume refined carbohydrates such as sugar, flour, and processed grains. These foods, not meat, are the real drivers of fat gain.

In fact, meat has a low to moderate insulin response. For example, beef’s insulin index is relatively low compared to carbohydrate-rich foods like fruits or bread. When compared to refined carbs, meat’s ability to raise insulin is minimal. Therefore, meat, especially in its unprocessed form, does not cause significant insulin spikes and, by extension, does not directly contribute to obesity.

Type 2 diabetes is primarily a blood glucose issue — it’s characterized by high blood sugar levels, not fat storage. Since meat is very low in carbohydrates, it doesn’t cause spikes in blood sugar. It’s actually carbohydrates, particularly refined ones, that have a far more significant impact on blood glucose levels. In studies measuring the glucose response to various foods, meat produced one of the lowest blood sugar responses of all foods tested.

The problem arises when meat is paired with sugar-laden sauces, batter, or served on a refined-carb bun. These processed foods raise blood sugar and insulin levels, creating a situation where eating meat alongside high-carb foods might contribute to metabolic issues like diabetes. But meat itself? It’s simply too low in carbohydrates to raise blood glucose significantly.

The claim that meat causes hypertension (high blood pressure) is not supported by the science. In fact, research suggests that meat consumption is not a significant factor in blood pressure regulation.

Tragically, when you walk into a doctor’s office with high blood pressure, the first two suggestions are medications like ACE inhibitors or beta-blockers and to eat less meat. The damage this does to an already struggling body is mind-blowing.

A 2020 meta-analysis of thirty-six randomized controlled trials (RCTs) found that there was no effect of red meat on blood pressure when compared to other protein sources. This large-scale analysis debunked the common myth that consuming red meat automatically leads to high blood pressure, showing that other dietary factors are more likely to be responsible.

Another recent study highlighted that low-carbohydrate diets (which often include meat) led to significant reductions in blood pressure and reduced reliance on blood pressure medications.

The explanation for these benefits lies in the role of insulin: high insulin levels, which are typically triggered by diets rich in refined carbohydrates, are known to raise blood pressure by causing the kidneys to retain more sodium. By reducing carbohydrate intake, insulin levels drop, leading to improvements in blood pressure regulation.

There’s a common misconception that high-protein diets, especially those rich in meat, can cause kidney damage or exacerbate kidney disease. However, the evidence supporting this claim is weak, and the reality is that meat—when consumed as part of a balanced diet—doesn’t pose a significant risk to healthy kidneys.

The number one risk factor for kidney failure is hyperglycemia (high blood sugar), and the number two risk factor is hypertension (high blood pressure). These conditions have a far greater impact on kidney function than dietary protein intake. Healthy kidneys are well-equipped to process high amounts of protein, but they are not designed to handle prolonged periods of high glucose levels or elevated blood pressure.

A 1930 study of two men who ate a 100-percent-meat diet for a full year found that both had no signs of kidney problems whatsoever, despite their extreme protein intake. Fast forward to modern times, and studies of bodybuilders consuming 2.2 to 3 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day (about three times the recommended daily intake) for months on end found that their kidney function remained normal.

The real culprits behind kidney disease are high blood sugar and high blood pressure, not meat. As long as kidney function is normal, a high-protein diet can be safely handled by healthy kidneys. If you’re worried about kidney disease, focusing on controlling blood glucose levels and blood pressure will be far more beneficial than restricting meat.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

When it comes to red meat, the science is clear: the fear surrounding it is largely unfounded, built on shaky studies, industry agendas, and decades of misinformation.

Meat isn’t the enemy — in fact, it’s one of the most nutrient-dense, biologically appropriate foods you can eat as a human being. Our bodies evolved to thrive on it. The myths about saturated fat, heart disease, cancer, and digestion fall apart when you examine the evidence closely, and what remains is simple: meat is real food. It provides complete protein, essential fats, vital nutrients, and supports everything from brain function to hormone production.

Of course, quality matters. Meat from well-raised, healthy animals is always the better choice. And like any food, it’s best enjoyed as part of a diet that’s rooted in whole, unprocessed, nutrient-dense options.

So next time you hear someone say “Red meat is bad for you,” you’ll know the truth: it’s not only safe — it’s one of nature’s greatest gifts.

Meat isn’t the enemy — in fact, it’s one of the most nutrient-dense, biologically appropriate foods you can eat as a human being. Our bodies evolved to thrive on it. The myths about saturated fat, heart disease, cancer, and digestion fall apart when you examine the evidence closely, and what remains is simple: meat is real food. It provides complete protein, essential fats, vital nutrients, and supports everything from brain function to hormone production.

While it would be nice to attribute these myths to the limits of epidemiological studies, the truth is, there’s a lot of foul play involved — including heavy industry influence, like The Seventh-Day Adventists funding a significant portion of plant-based studies to fit their religious narrative.

Half of the studies on unprocessed red meat suggested a connection to cancer, while the other half did not. That’s not strong evidence: it’s literally as meaningful as a coin toss.

Studies on processed meat were only slightly more consistent, but even then, these types of studies can only hint at possibilities. We also know that processed foods in general, are not healthy.

Learning from failure is nature’s most efficient learning mechanism, yet as adults, we try to avoid failure at all costs. Instead, we should learn how to fail the correct way.

Explore practical strategies on how to overcome laziness, embracing laziness as natural and tackling it with rest, planning, and reframing success.”

The victim mentality and learned helplessness are two different concepts that are often misused. Learned Helpless is a neurological condition that affects all of us to some degree

Here are the 5 best self-improvement books of all time that actually work.

Maintaining physical health is a lifelong endeavor, but there are some easy evidence-based activities that can be implemented immediately for a healthier lifestyle.

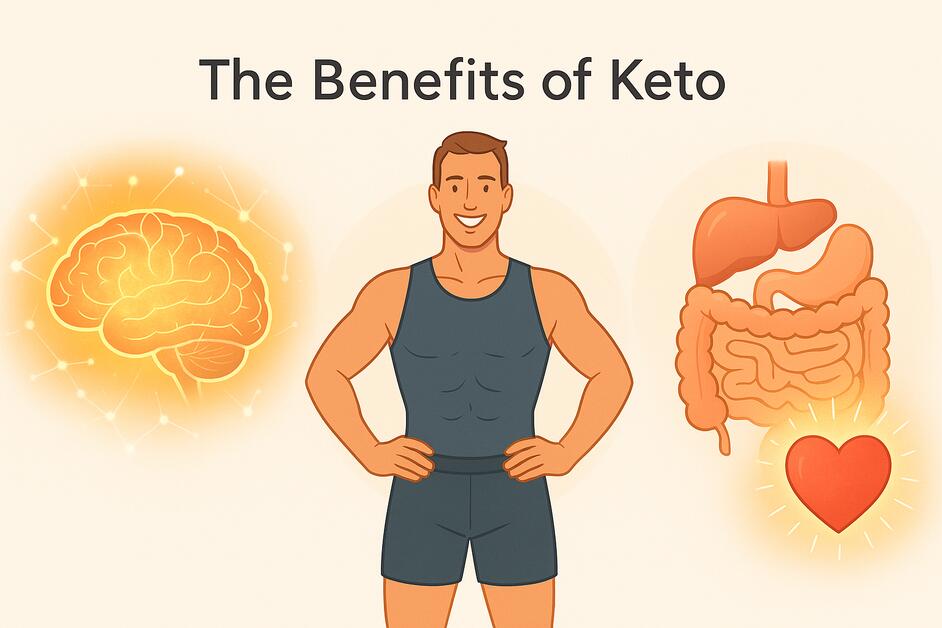

The benefits of the ketogenic diet include weight loss, improved energy, and better blood sugar control. It promotes fat burning and mental clarity.

© 2025 Modern Mind Masters - All Rights Reserved

You’ll Learn:

Effective Immediately: 5 Powerful Changes Now, To Improve Your Life Tomorrow.

Click the purple button and we’ll email you your free copy.