Is ADHD Behind Analysis Paralysis?

Analysis paralysis occurs when overanalyzing a situation results in a lack of ability to make a decision. These effects are worsened in those with ADHD, leading to ADHD paralysis.

Ketamine therapy shows potential for rapidly relieving mental health issues like depression and PTSD, particularly for treatment-resistant cases.

Ketamine blocks NMDA receptors and boosts BDNF, enhancing neuroplasticity, unlike slower-acting antidepressants.

Caution and supervision are crucial due to ketamine’s high abuse potential, dissociative effects, and possible long-term neurological changes.

From a Schedule III prohibited drug to the World Health Organization’s List of Essential Medicines, ketamine has had a rollercoaster history. While its popularity soared in the 1970s as the recreational drug of choice in the club and party scene, “Special K”, as it was then known, has morphed into a drug of high potential in the war against mental health.

The landscape surrounding ketamine has changed immensely in the past 10 to 20 years; where it was once a drug of abuse like PCP, clinical research has revealed its potential for mental health, from treating depression and suicidality to overcoming PTSD.

Although some look to ketamine as a miracle drug, it is not without its drawbacks. Ketamine has a very high potential for abuse, and due to its nature of activating excitatory neurons, can result in mental distress and seizures for those prone to it.

This article will explore the potential of ketamine and ketamine therapy in the fight against mental health and depression, highlighting the mechanism of action, benefits, potential side effects, and how it can change the neural states of the brain for the better.

Ketamine is a dissociative anesthetic, a compound that induces a state of dissociation (separation) between the mind and body. It provides multiple “planes” (levels) of anesthesia, from lowered consciousness but awake to fully unconsciousness, hence why ketamine is widely used as an anesthetic.

The stage between awake and deeply anesthetized, known as dissociation, results in a level of awareness similar to when we are dreaming, and is the state sought after for the treatment of mental health issues such as depression, suicidality, and PTSD.

Ketamine goes by many street names, including Jet K, Kit Kat, Purple, Special K, Special La Coke, Super Acid, Super K, and Vitamin K. Recreational use of ketamine places it in the same category as other drugs of abuse, such as cocaine, PCP (phencyclidine), and meth.

Ketamine therapy, also known as ketamine-assisted therapy or ketamine-assisted psychotherapy, is a treatment approach that utilizes the potential psychiatric benefits of ketamine in a controlled and supervised environment. This typically involves the use of psychotherapy or counseling by a qualified professional to address various mental health conditions.

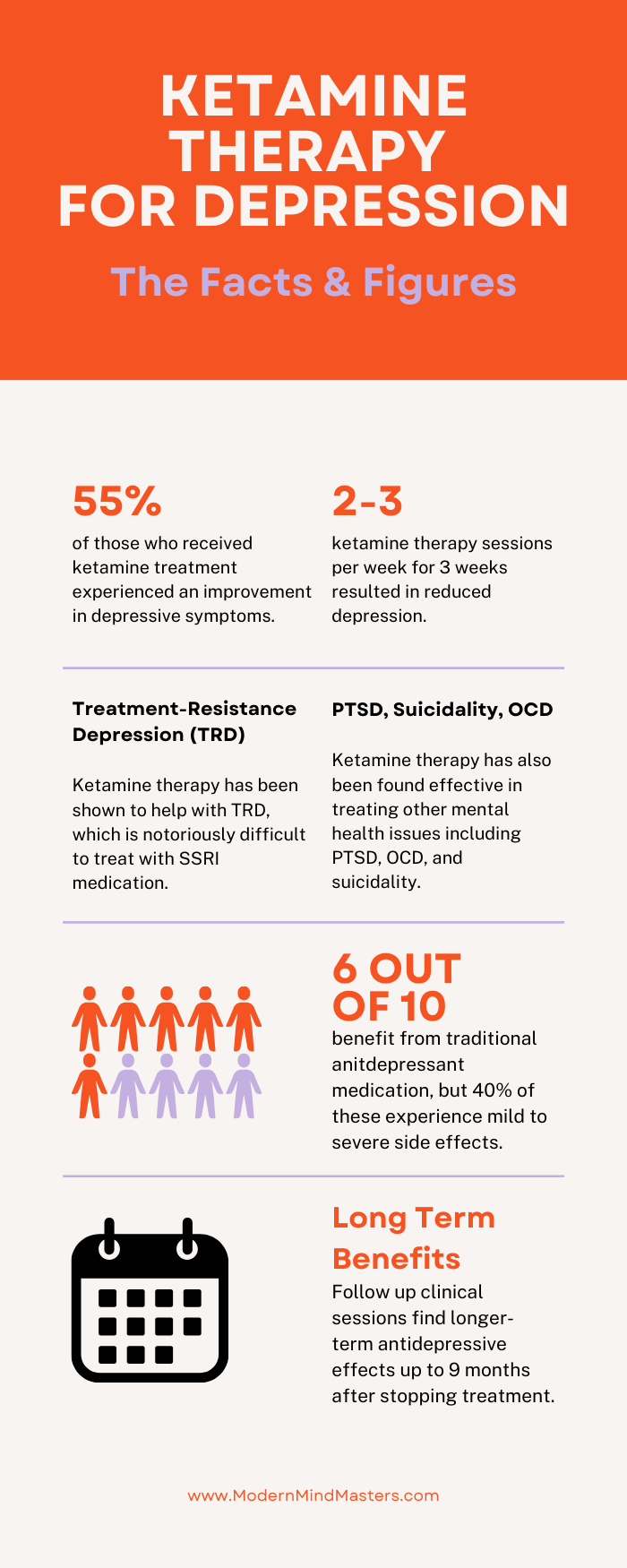

Ketamine therapy is primarily used to treat mood disorders, particularly treatment-resistant depression (TRD) and major depressive disorder (MDD), two conditions that are tricky to manage and typically treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and other antidepressant drugs. Unfortunately, such drugs have a success rate of only 60% and are frequently accompanied by mild to severe side effects.

Ketamine therapy and ketamine infusion therapy are often used interchangeably, but ketamine infusion therapy is a more specific type of ketamine therapy.

Whereas typical ketamine therapy refers to various forms of ketamine-based treatments, including ketamine infusion therapy, intranasal ketamine, and oral ketamine, ketamine infusion therapy refers specifically to the intravenous administration of ketamine into the bloodstream through an IV line.

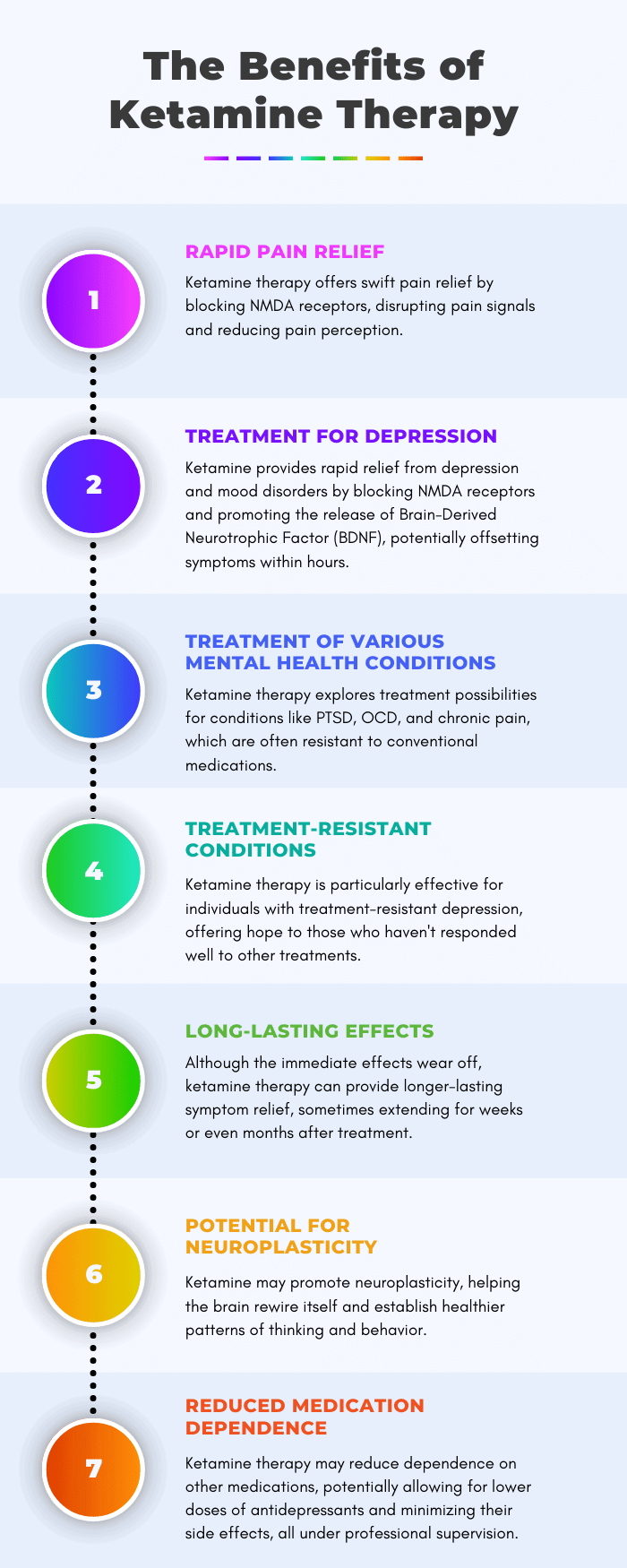

Ketamine infusion therapy results in a rapid onset of action, as ketamine is delivered directly into the bloodstream instead of having to wait for it to be ingested with a pill, making it particularly useful for rapid pain relief.

Ketamine is an NMDA (N-methyl-D-aspartate) receptor antagonist, meaning it blocks the activity of NMDA receptors which play a key role in the transmission of pain signals. By modulating these receptors, ketamine can disrupt the pain signaling process and reduce pain perception.

The use of ketamine outside professional medical supervision, however, reduces the ability to monitor a patient during treatment, enhancing the probability of toxicity and abuse. It is hoped that smart dosing regimens, patient and doctor training, and close monitoring of drug dispensing will one day make at-home ketamine treatments successful.

Ketamine has been shown to provide rapid relief from symptoms of depression, anxiety, stress, and certain other mood disorders, with some individuals experiencing improvements after just a few hours, significantly faster than many traditional antidepressant medications.

Not only does ketamine block NMDA receptors, but it also increases the release of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), a protein that promotes the growth of neurons. BDNF is thought to play a role in neuroplasticity, a mechanism that can reduce the effects of depression.

Unlike other antidepressant drugs, which can take weeks or months to start working, ketamine has a very rapid mechanism of action, meaning it can begin to offset depressive symptoms in days or even hours.

Besides depression and anxiety, ketamine therapy is being explored as a potential treatment for conditions like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and chronic pain, conditions that are notoriously difficult to treat with current medications.

One of the most promising aspects of ketamine therapy is how effective it is for individuals who have not responded well to other treatments, including medications and psychotherapy, a type of depression known as treatment-resistant depression.

Typical antidepressant medication is effective in 60% of cases, although it is not without its side effects. While it is great that 60% will see improvements, ketamine provides a glimmer of hope for the remaining 40% who desperately seek an escape from their depression.

While the immediate effects of ketamine infusion may wear off within hours to days, multiple studies report longer-lasting relief from their symptoms, sometimes weeks or months after treatment.

Long-term studies have measured the effect of taking ketamine twice per week for three weeks, finding not only some immediate relief from depression after the first course, but having done it consistently for multiple weeks and then stopping, the relief continued for months afterward.

This study found that 65.7% of patients who completed a ketamine infusion schedule three times weekly over 12 days achieved response and remission rates of 80.3% and 78.9%, respectively, after a 9-month follow-up consultation.

Similar to other therapies, such as psychedelic or psilocybin-based therapies, ketamine is thought to promote neural plasticity, helping the brain rewire itself and form new and healthier patterns of thinking and behavior.

Neuroplasticity requires a change in the nervous system, a difficult task that is energetically demanding.

When you generate an unusual pattern of activity (such as different finger movements when learning to play the piano), neurons in the brain fire in a way that is atypical for them. These neurons bind to glutamate, an amino acid that plays a key role in stimulating and facilitating neuronal communication, resulting in greater levels of neuroplasticity.

You will have experienced this firsthand when learning to perform a new activity, where new movements feel sluggish and require a lot of concentration and energy. Eventually, it becomes easier as the glutamate receptors recruit other receptors, enabling the behavior to occur without having to do it in such a metabolically demanding way.

For some individuals, ketamine therapy may reduce their dependence on other medications, or at least lower doses of antidepressants, thereby reducing their potential side effects.

Ketamine is generally considered to have a lower risk of physical dependence compared to other substances used to treat mental health conditions, but successful ketamine-based therapies require a professional to help realize these benefits effectively while minimizing the risks.

Of most interest to researchers and therapists is ketamine’s potential in treating depression, a crippling condition that has proven difficult to treat effectively.

Because of the intensity and prevalence of side effects from typical antidepressant drugs, from sexual dysfunction to fatigue and drowsiness, an alternative treatment that does away with these side effects is of high value.

Common antidepressant drugs, such as SSRIs, increase certain monoamines, a group of neurotransmitters in the central nervous system that regulate mood and emotions. Prozac and Zoloft, for example, increase serotonin, while Wellbutrin increases dopamine and norepinephrine, providing relief for certain symptoms of depression.

Research shows that drugs that aim to increase monoamines work in about 40% of those who use them to treat depression, and are often accompanied by side effects that can be worse than the original symptoms they were trying to treat. As a result, the search has continued for better alternatives.

That is where ketamine has piqued interest. One of the first thorough studies was performed in 2000, where a paper titled “Antidepressant effects of ketamine in depressed patients”, found that a clinical dose of half a milligram of ketamine per kilogram of body weight reduced depressive symptoms within just a few minutes, with the effects lasting for several days.

The duration of the effects of ketamine varies depending on several factors, including the dose administered, the method of administration, and an individual’s metabolism.

When administered intravenously, where ketamine enters the bloodstream immediately, the effects of ketamine usually onset rapidly, peaking within 5 to 10 minutes.

The intense psychoactive effects can last for approximately 30 to 60 minutes. After this, individuals typically experience a gradual return to baseline consciousness over a few hours, although residual effects may persist for longer.

Ketamine can also be administered orally, through pills or tabs placed under the tongue, although these methods have a slower onset and longer duration of effects lasting several hours compared to more direct administration.

While the short-term effects of ketamine, such as dissociation and rapid relief from pain and depression, typically last hours, studies have found longer-term antidepressant effects and neuroplasticity changes up to nine months later. More research is needed to determine the effects (both positive and negative) of long-term consistent ketamine use.

As with any drug-based treatment, the number of ketamine treatments for depression can vary widely from person to person, depending on factors such as an individual’s specific condition, the severity of their depression, their response to treatment, and the type of treatment used.

When tested on mice, the antidepressant effects were noticeable after a single treatment, reinforcing the rapid relief impacts of ketamine treatment.

Of the few longer-term studies that have been performed, however, it appears a treatment schedule of taking ketamine twice per week for a duration of three weeks is enough to provide both short and longer-term benefits (at least up to nine months that was tested in the study).

For patients who have used this twice-weekly schedule consistently for multiple weeks, suddenly stopping all treatments did not immediately reduce the antidepressant effects. Some of the effects endured months after ceasing treatment.

More longer-term studies are needed to fully realize the longer-term effects, but early research shows promise for ketamine treatment at a 12-week twice-a-week schedule repeated periodically, perhaps annually, depending on the needs of the individual.

Ketamine is not technically an opioid; it is a dissociative anesthetic that works differently from opioids in terms of its mechanism of action and effects on the body and brain. It does, however, utilize opioid pathways to produce its antidepressant effects, opening the potential for opioid abuse if not controlled.

Ketamine binds to receptors in the opioid pathway, which creates certain effects like pain relief, changes in psychic states, dissociation, anesthesia, and altered states of consciousness that recreational drug users often seek.

This degree of dissociation usually occurs at levels of 1-2 milligrams per kilo of bodyweight (two to four times the level recommended in a clinical ketamine therapy setting), where full binding of all receptors that ketamine can bind to occurs, including both the glutamate related system and the opioid system.

This study tested if blocking the opioid pathway was required to experience the antidepressant effects of ketamine. Clinicians blocked the opioid pathway using a drug called Naltrexone and found that the anti-depressant effects of ketamine were no longer observed when blocked, indicating that the blocking of the opioid pathway is essential to experiencing relief from depression.

Because of its proven effectiveness, some individuals have attempted to use ketamine outside of clinical settings to self-treat their depression. However, this practice introduces a significant departure from its intended medical use, which raises the risk of misuse and abuse.

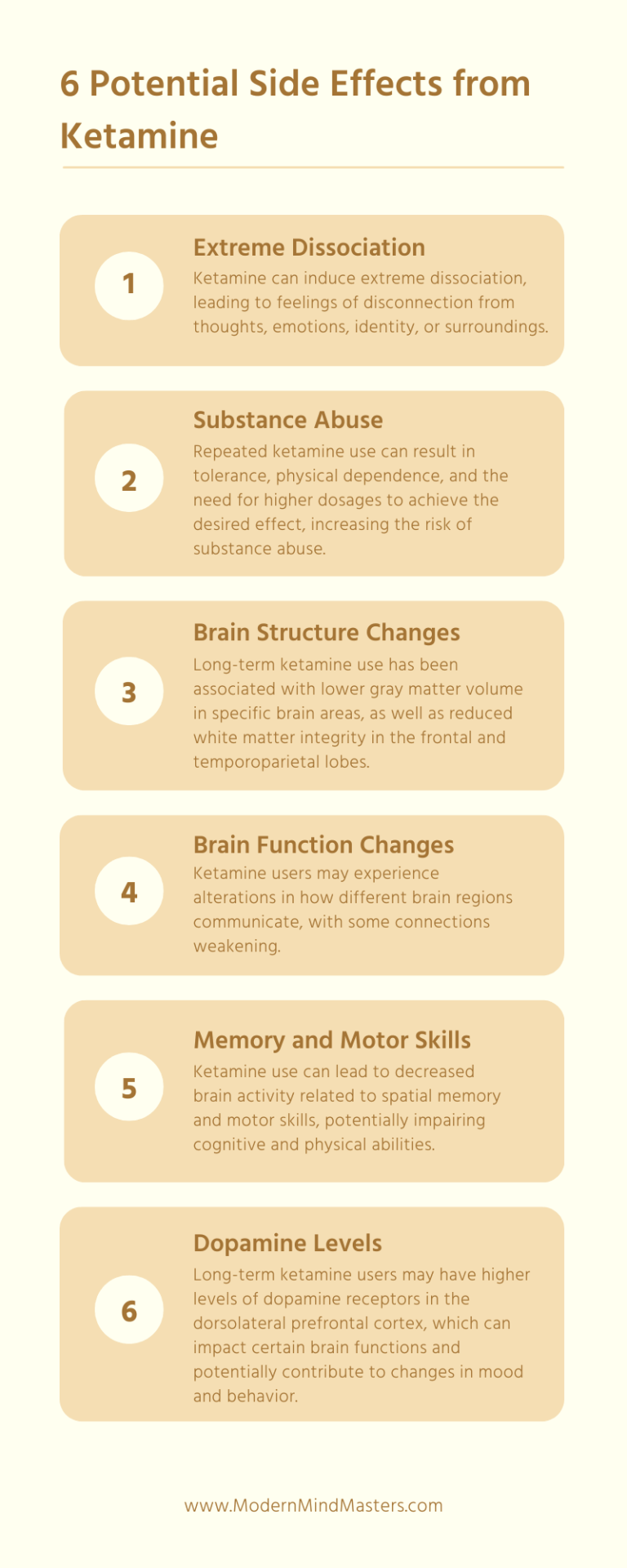

Dissociation, where a person feels disconnected from their thoughts, emotions, identity, or surroundings, often resulting in a sense of detachment or unreality, is a hallmark effect of ketamine. Recreational ketamine users often chase this “out of body” experience.

But dissociation is also one of the primary symptoms of PTSD and trauma, where it can create intensely unpleasant feelings such as flashbacks, psychosis, and schizophrenia, especially in those already predisposed to such mental health conditions.

As far as is known, dissociation is due to an uncoupling of certain brain circuits, in particular neocortical brain circuits (those associated with action planning, speech generation, and sensory perception) that connect to subcortical regions. When under the influence of ketamine, there seems to be an uncoupling of these networks that alters the neural rhythm of the brain.

In particular, ketamine appears to completely abolish the alpha state, where the brain is alert but calm, and thoughts are free-flowing, lasting for the active duration of the drug (typically one to two hours).

A theta brain pattern emerges in its place, where the brain enters a dream-like state at the border between wakefulness and sleep. You’ll recognize this state if you’ve ever woken up after kicking your leg.

For many, this dissociative change in brain states is unpleasant and can lead to significant mental discomfort.

Repeated ketamine use is thought to lead to some degree of tolerance, where continued and frequent use increases physical dependence and increasing dosages to achieve the same effect. Hence the importance of only considering taking ketamine in a therapy-based environment, where professionals can monitor and adjust your dosage for maximum benefit while mitigating the potential for adverse effects.

Frequent users have reported withdrawal syndromes when ketamine use stops, leading to unpleasant symptoms such as depression, excessive sleepiness, and drug cravings.

Research has found that ketamine can cause longer-term changes in the brain, affecting various mental processes and dysregulation in balancing neurotransmitters responsible for mood, such as dopamine and serotonin. Other changes include:

Ketamine therapy, when performed under controlled and supervised conditions, offers a range of benefits; it provides rapid pain relief and, more importantly, has shown remarkable efficacy in treating conditions like depression, anxiety, PTSD, and chronic pain.

Of particular interest is its ability to help individuals who have struggled with treatment-resistant conditions, especially depression, offering hope to those who haven’t found relief through conventional methods.

Like other forms of drug therapy (psilocybin and other psychedelics), ketamine may contribute to neuroplasticity, allowing the brain to form new, healthier patterns of thinking and behavior while reducing the dependence on other medications and avoiding their often crippling side effects.

However, ketamine therapy, especially outside the clinical setting, is not without its challenges. Misuse and abuse are significant concerns due to their high potential for abuse and the risk of severe mental distress and seizures in susceptible individuals. Recreational and self-medicating use of ketamine carries significant health risks and should be strongly discouraged.

Long-term neurological changes associated with ketamine use, such as alterations in brain structure and function, need careful consideration. These changes underscore the importance of using ketamine exclusively in clinical settings, where professionals can tailor treatments to maximize benefits while minimizing risks.

In the realm of mental health, ketamine stands as a remarkable breakthrough, offering hope to many who have been battling the debilitating effects of conditions like depression. However, its journey from a club drug to a therapeutic tool reminds us of the need for responsible and controlled use, guided by medical professionals. The future of ketamine therapy holds promise, but it must be approached with caution and respect.

Ketamine therapy is a treatment approach that utilizes the potential psychiatric benefits of ketamine in a controlled and supervised environment.

Ketamine blocks NMDA receptors while also releasing Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), a protein that promotes the growth of neurons. BDNF is thought to play a role in neuroplasticity, a mechanism that can reduce the effects of depression.

Ketamine is not technically an opioid; it is a dissociative anesthetic that works differently from opioids. It does, however, utilize opioid pathways to produce its antidepressant effects, opening the potential for opioid abuse if not controlled.

Analysis paralysis occurs when overanalyzing a situation results in a lack of ability to make a decision. These effects are worsened in those with ADHD, leading to ADHD paralysis.

By resetting dopamine levels back to healthy baseline levels, we can boost cognitive performance and improve mental health.

Too much dopamine can be a bad thing; overindulgence will lead to lower motivation, addiction, and even depression. Learn how to dopamine detox with these 5 activities

Retirement will come sooner than you imagine. Learn why building retirement savings is vital and how much you need to start saving today.

Knowledge is not power without action, and habits form the consistent actions that compound over time to guarantee success.

Logical and rational thoughts stem from the conscious mind, whereas emotional and impulsive thoughts are induced from the subconscious mind, which is beyond our control.

© 2025 Modern Mind Masters - All Rights Reserved

You’ll Learn:

Effective Immediately: 5 Powerful Changes Now, To Improve Your Life Tomorrow.

Click the purple button and we’ll email you your free copy.