The Benefits of Grounding – What The Science Says

The benefits of grounding have been scientifically studied and include reductions in inflammation, diabetes, and stress.

In an age where chronic disease and dependency on medication are rampant, a hard truth confronts us: many of our health woes are self-inflicted. The increasing prevalence of lifestyle-related diseases paints a grim picture of our societal neglect of the fundamental pillars of health – sleep, diet, and exercise.

While we chase after advanced medical treatments and rely heavily on pharmaceutical solutions, the irony is stark: the key to preventing these ailments lies within our grasp yet remains underutilized.

We stand at a crossroads where the need to reclaim control over our health has never been more urgent. By re-embracing the basics of sleep, diet, and exercise, we can unlock a more profound and effective form of preventative healthcare, without the often debilitating side effects of drugs and medications.

This blog post delves into the critical yet often overlooked power of the three pillars of health and how you can best utilize them with simple everyday routines to fortify your body and brain against these self-imposed and rampant killer diseases.

These pillars are not just foundational; they are transformative, offering a path to a healthier, more vibrant life. It’s time to break free from the shackles of our own making and harness the full power of these simple, yet life-altering principles.

Despite advances in medicinal science and increasing awareness of health, the world is getting sicker; over the last 30 years, deaths and disability from cardiovascular disease have been steadily rising across the globe. In 2019 alone, cardiovascular disease was responsible for one-third of all deaths worldwide.

Rates of diabetes have increased from 108 million in 1980 to 422 million in 2014, rising more rapidly in low- and middle-income countries than in high-income ones.

It is not just physical health that has dived; depression disorders are also at an all-time high, especially after the mental impacts exhibited by COVID lockdowns.

An NHS survey in 2023 found that one in five 8- to 16-year-olds in England had a probable mental disorder, while the number who are out of work with mental health conditions has risen by a third between 2019 and 2023.

An increase in illness and disease naturally results in an increased dependency on medication.

In England, about 15% of people take five or more prescription drugs daily. In North America, the figure is 20% for those aged 40-79.

And the older we get, the worse it becomes. Of Americans who are 65 or older, two-thirds take at least five medications each day, and in Canada, a quarter of over-65s take ten or more.

While medication is, in theory, a good thing, treating illnesses and curing symptoms, not all of those prescriptions are beneficial. It is estimated that half of older Canadians take at least one medication that is, in some way, inappropriate, and a review of overprescribing in England in 2021 concluded that at least 10% of prescriptions handed out by family doctors, pharmacists, and the like should probably not have been issued.

The problem is the side effects that occur from most prescription drugs, even when properly prescribed. SSRIs used to treat depression, for example, induce bothersome side effects in 38% of users, 25% of which are classified as “very bothersome”. To make matters worse, the more medicines one takes, the more side effects are experienced.

The increasing use of medication and the corresponding increase in side effects means hospitals must divert crucial resources to treat them. A recent study at a hospital in Liverpool, for example, found that nearly one in five hospital admissions was caused by adverse reactions to drugs.

Aside from the obvious physical and mental costs associated with increased illness and medication, the financial burdens these states place on states are substantial: studies have estimated that the social, economic, and health burdens of sleep mental health disorders cost governments trillions of dollars each year.

The Western world has largely become a victim of its own success, where the demands of family and careers strain our sleep patterns, diets consist of quick, convenient, and tasty processed foods, and exercise is seen as optional if you have time.

Meanwhile, pharmaceutical companies are taking advantage by charging large sums of money to treat illnesses that could have been avoided through a healthier lifestyle.

Instead of medicating for diabetes, cardiac disease, and even cancer, diet, sleep, and exercise can provide a more effective preventative medication than many drugs, with no side effects. Even the risk of developing cancer, an almost inevitable byproduct of biological processes, can be significantly reduced through diet, as we will see.

Fortunately, there is a way out, and it requires going back to basics. I’m sure you’ve heard of the importance of diet, sleep, and exercise on health, with suggestions to incorporate more fruit and veg into your diet, obtain a full night’s sleep, and exercise once or twice a week.

These suggestions go beyond mere common sense; abundant studies have made it irrevocably clear that there are vast mental and physical health benefits when we improve our diet, sleep, and exercise routines. And when just one component is missing, a plethora of health issues appear over time, increasing susceptibility to chronic illnesses ranging from diabetes to cancer.

Let’s start with the first component of the Holy Trinity of health – sleep. This is probably the simplest of the three components to fix; after all, who doesn’t want more sleep?

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 1 in 3 adults in the United States alone reported not getting enough rest or sleep every day. That is a colossal third of the US population whose long-term health is compromised due to ineffective sleep patterns.

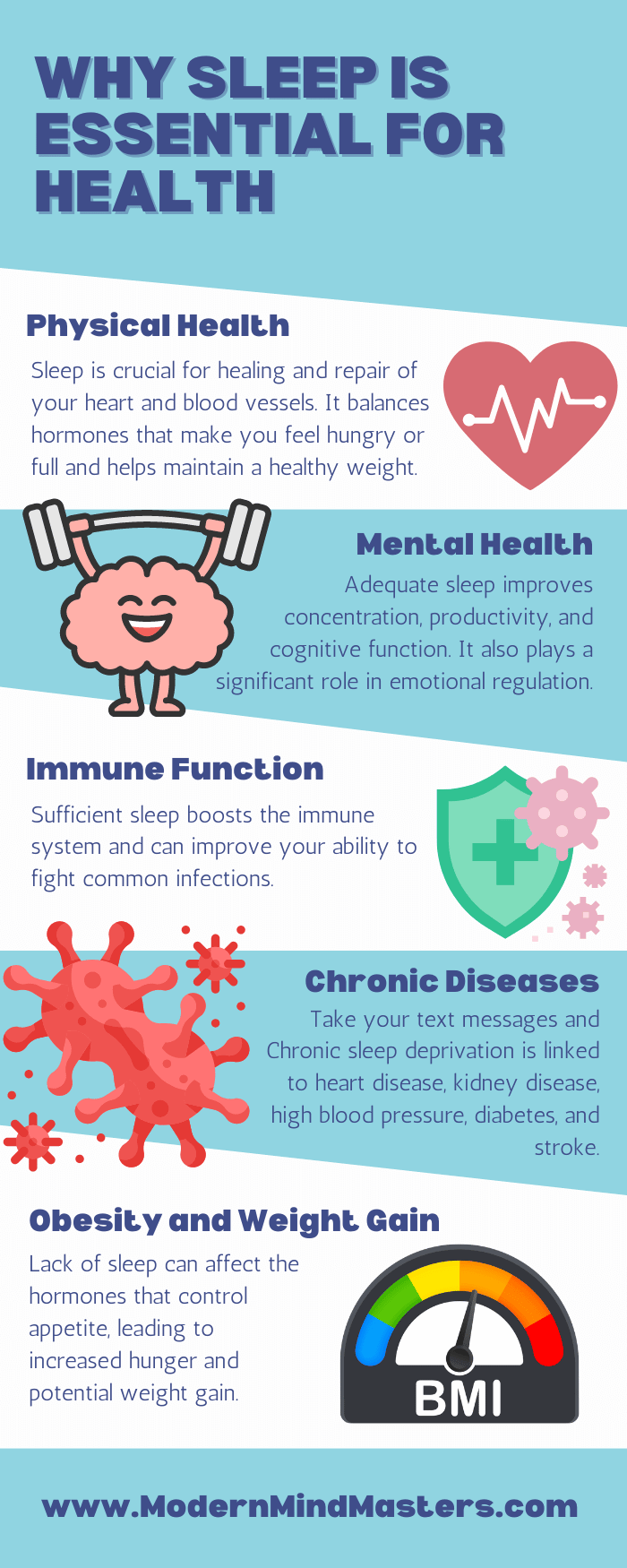

New studies are continually confirming the relationship between inadequate sleep and a range of disorders, such as hypertension (high blood pressure), obesity and type-2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and impaired immune functioning. Oversleeping also has its own problems.

While the advice that sleep is good for your health is nothing new, researchers are now beginning to probe more deeply into the cellular and subcellular effects of disrupted sleep, including the effects on metabolism, hormone regulation, and gene expression.

Despite the rapid acceleration in research during the past few decades, inadequate sleep due to sleep disorders, work schedules, and chaotic lifestyles continues to threaten both health and safety.

With careers, family, and friends, people have come to value time so much that sleep is now thought of as an annoying interference, as opposed to an essential component of health. Unfortunately, this view is an open road to poor health.

Any medication that could turn you from a mumbling and yawning mess to fresh as a daisy and ready to tackle the day ahead in just eight hours would likely be the most consumed and valuable medication on the market. Yet this is exactly the power achievable from a good night’s rest.

When we sleep, many highly complex and not yet fully understood neurological processes occur. One crucial process is memory consolidation, where the brain processes and organizes information acquired throughout the day, including the transfer of short-term memories to long-term storage, strengthening neural connections, and integrating new knowledge with existing information.

Essentially, sleep is where we learn, and the mechanism behind this is neural plasticity, the brain’s ability to adapt and reorganize its connections in response to learning and experience. During sleep, the brain undergoes processes that facilitate synaptic plasticity, allowing for more efficient learning and memory formation.

Sleep is also crucial for waking cognition; the ability to think clearly, be alert, and sustain attention is highly dependent on sleep.

Research led by Dr. Dinges and fellow scientists reveals a rapid decline in cognitive performance and sustained attention after surpassing 16 hours of consecutive wakefulness. Moreover, deficits in sleep due to partial deprivation can accumulate, gradually leading to a decline in alertness over time.

The exact neurological processes underlying these neuroplastic changes are still not fully known, but these energy-intensive processes create metabolic toxic waste in the brain, for which sleep is essential to flush them out.

Scans have revealed that cerebrospinal fluid in the brain’s extracellular space is flushed around to clear metabolic garbage. Studies in mice brains without these channels for flushing did poorly at clearing waste, including amyloid protein, the buildup of which is linked to Alzheimer’s disease. They cleared waste 70% more slowly than mice possessing the channels.

Without adequate sleep, you allow the buildup of metabolic waste material, preventing you from maximizing your cognitive performance while increasing the toxicity of the brain.

With depressive and anxiety disorders affecting more than 300 million globally, scientists the world over are exploring this comorbidity in depth to find ways to ease this burden.

The relationship between sleep and mental health is bi-directional; for instance, sleep disturbances were observed in individuals with anxiety and depression. Additionally, having a sleep disturbance may predict the development of an anxiety disorder and depression.

One study observed how “high’ and “low” performance of a task is perceived to be demands on the extent of sleep deprivation.

Those who were sleep-deprived responded to low stressors in much the same way that people without any sleep deprivation responded to high stressors. In other words, tasks may seem more emotionally and socially difficult when sleep-deprived than when well-rested.

While the exact mechanisms behind the relationship between poor sleep quality and depression/anxiety are not fully known, neural circuits such as the corticolimbic circuit, which is related to difficulties in affective reactivity and regularity, are affected by poor sleep quality.

Furthermore, the dopaminergic systems that facilitate reward and motivation have also been shown to be negatively affected by poor sleep quality.

Hopefully, it is no surprise to you to hear that poor sleep negatively affects brain functioning and health, which leaves the question of how much sleep is sufficient to avoid these detriments.

While eight hours of sleep is frequently cited as a minimum, the consensus among experts across thousands of evaluations, studies, and scientific articles identifies a sweet spot for the average healthy adult of between seven and seven and a half hours.

This number varies by age; pensioners, for example, may require less sleep, while adolescents will likely need more. But for the average adult, a great starting place is between seven and seven and a half hours.

While an exact answer for your situation may not be possible, you have a pretty good sleep gauge built into you, that is, how tired you feel when waking up. If you still feel tired an hour after waking, it is clear that your body and brain require more sleep. If it only takes you 30 minutes or so to fully engage, you are likely on the right track.

Listen to your body and brain, and identify any signals that they may be craving more or less sleep.

While the first pillar of health, sleep, may prove simple to improve, the second, diet, often proves the most challenging.

The significance of diet in maintaining health is so profound that it has given rise to an entirely new branch of research known as nutritional psychiatry. This emerging field explores how various aspects of diet—such as eating patterns, food quality, and nutritional components—can influence mental health and sleep, offering potential benefits without relying on medication.

Among the key findings in nutritional psychiatry is the importance of the gut microbiome in maintaining human health, referring to the trillions of microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other microbes, that inhabit the gastrointestinal tract.

Research has pinpointed the microbiota-gut-brain axis as the principal nutrient-driven mechanism that plays a critical role in regulating sleep and mental health. The image below illustrates other vital functions performed by a healthy gut microbiome.

While the mechanism of gut microbiomes and intestinal health may be complex, identifying a healthy diet is mostly common sense.

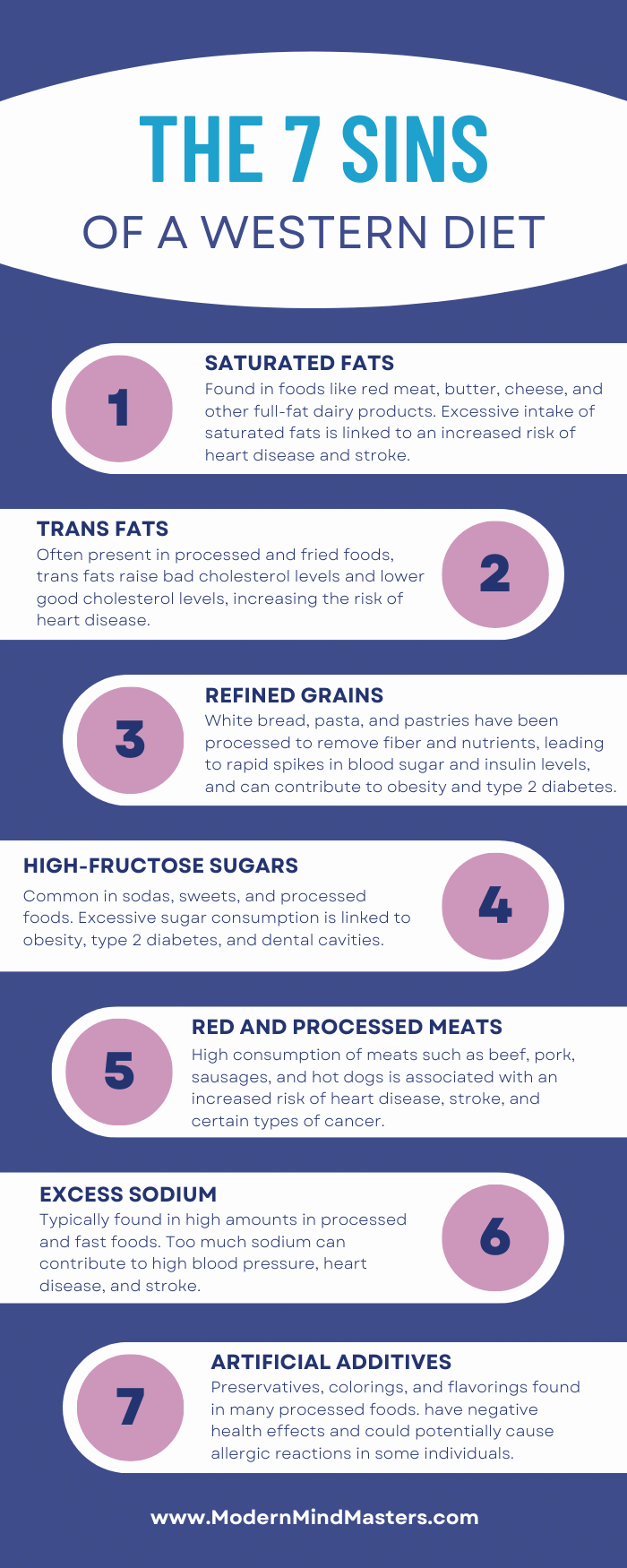

It should come as no surprise that a healthy diet contains a high intake of vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and fish, while unhealthy diets include increased consumption of Western-type foods such as those high in fat and sugar, which are often processed.

Westerners have fallen victim to their own success; with busy lifestyles and well-compensated careers, fast, convenient, and satisfying foods, all of which tend to be unhealthy, dominate modern diets.

Today, ultra-processed foods make up 73% of the US food supply, according to Northeastern University’s Network Science Institute. While convenient and often tasty, processed foods contain high levels of saturated fatty acids, which have been shown to result in negative alterations in the gut microbiome.

Such processed foods are positively associated with mental health afflictions, such as increased risks of depression, anxiety, and ADHD, as well as physical health troubles, such as increased circulation of inflammatory markers, diabetes, heart disease, and cancer.

While the US has a bad reputation for unhealthy diets, the UK is not much better. A large-scale study on 500,000 participants aged 40-69 found that only 7.9% could be classified as having a healthy/good quality diet, an embarrassing rate for a country that prides itself on its National Health Service.

Healthy and high-quality diets are generally high in fiber, which is known to be associated with beneficial changes in the gut microbiome composition.

Increased dietary fiber intake is thought to be beneficial for reducing or preventing inflammation, leading to an improvement in sleep and mental health outcomes.

This meta-analysis showed that healthy dietary patterns, defined by higher intakes of fruit, vegetables, fish, and whole grains, are negatively associated with an increased risk of depression. Interestingly, no effect was seen on symptoms of anxiety.

While diets such as Atkins and Keto have been shown to be fads, one diet has taken the scientific community by storm. The Mediterranean diet, a dietary pattern inspired by the traditional eating habits of people in the Mediterranean region, has been shown time and again to improve the gut microbiome and general health.

This study revealed a clear association between higher health scores and a diet rich in vegetables, fruits, and fish, paralleled by a reduced consumption of unprocessed red meat and processed meats. These dietary patterns are reflective of the core principles of most Mediterranean-style diets.

Food groups abundant in such diets, specifically vegetables and fruits, contain substantial amounts of fiber and polyphenols which are known to have anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, and prebiotic properties. They are also associated with reduced systemic inflammation markers.

Multiple studies have also shown negative associations between habitual meat consumption (both processed and unprocessed red meat) and sleep duration and quality, suspected to be caused by reduced ratios of tryptophan and tyrosine, two amino acids that serve as precursors for serotonin and melatonin, crucial for regulating mood, sleep, and overall cognitive function.

The third and final pillar, exercise, is perhaps the most unappreciated path to long-term health. While we are forced to eat and sleep every day, exercise often falls to the bottom of the priority list.

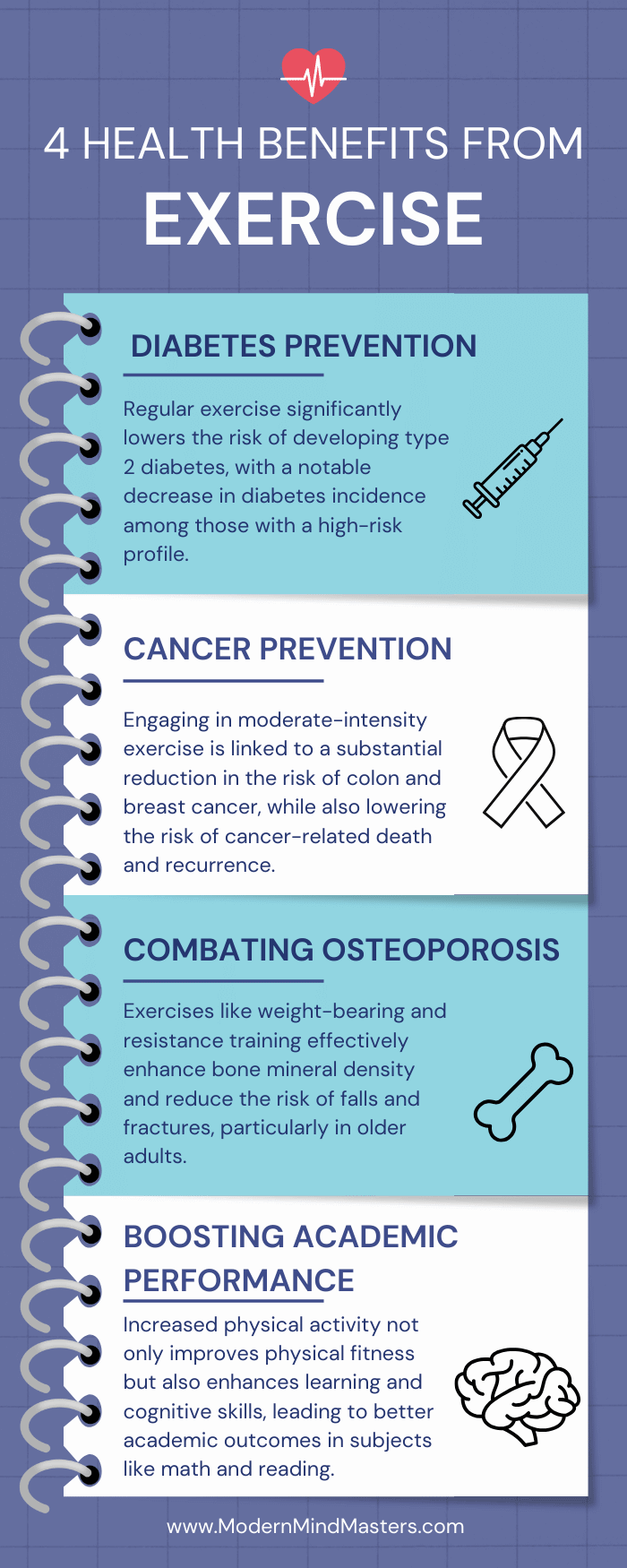

The detrimental impact of insufficient exercise might be more significant than commonly perceived. A Canadian study provided conclusive proof of the benefits of regular physical activity in both primary prevention—aiming to avert the emergence of diseases and health issues—and secondary prevention—focused on early detection and treatment to halt disease progression and complications. This is particularly true for a range of chronic conditions, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, hypertension, obesity, and depression.

Interestingly, there appears to be a linear relation between physical activity and health status, where further increases in physical activity (and hence fitness) result in additional improvements in health

Both men and women who reported increased levels of physical activity were found to have reductions in relative risk of death by 20%–35%, with even greater reductions of 50% for cardiovascular disease, the current leading cause of death globally.

Middle-aged women who engage in less than one hour of exercise per week were found to have a 52% increase in all-cause mortality and a terrifying 29% increase in cancer-related mortality, compared with physically active women.

Comparable findings were observed for other health conditions such as hypertension (high blood pressure) and obesity, where the severity of these conditions in inactive individuals was akin to that seen in moderate smokers. Indeed, individuals who engaged in exercise for one hour or less per week exhibited health issues on a par with moderate smokers.

Moreover, for individuals predisposed to cardiovascular disease due to factors like genetics or family history, certain studies indicate that they may be at a lower risk compared to those without these risk factors but who lead a sedentary lifestyle.

The encouraging aspect is that even minor enhancements in physical fitness can lead to substantial reductions in health risks. Modest increases in activity levels among previously inactive individuals have been linked to significant improvements in overall health.

A study highlighted this effect, revealing that participants who transitioned from a state of unfitness to fitness over five years experienced a remarkable 44% decrease in their relative risk of death, in contrast to those who continued to lead a sedentary lifestyle.

The advantages of primary prevention, particularly in averting diseases, are unmistakably evident. However, research also demonstrates significant benefits in secondary prevention for individuals already afflicted with diseases.

A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis, encompassing 48 clinical trials, disclosed that exercise, when compared to standard care, markedly decreased the likelihood of premature death from any cause, with a particularly notable impact on reducing fatalities related to cardiovascular disease.

To put this in context, an energy expenditure of about 1600 calories per week was found to halt the progression of coronary artery disease, and an expenditure of 2200 calories per week showed a reduction in the buildup of fatty deposits in patients with heart disease.

Similar studies have found that low-intensity exercise training (exercise at less than 45% of maximum aerobic power) is associated with improvements in health status among patients with cardiovascular disease. However, the minimum training intensity recommended for patients with heart disease is generally 45% of heart rate reserve.

With nearly half a billion suffering from diabetes globally, it is of great promise that the role of exercise in mitigating the effects of diabetes is becoming increasingly evident. Both aerobic and resistance exercises have shown promising associations with a decreased risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

In a comprehensive prospective study, each incremental increase of 500 calories in weekly energy expenditure was linked to a notable 6% reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes, underscoring the importance of adopting an active lifestyle in the quest for diabetes prevention.

Furthermore, this positive effect was particularly pronounced among individuals at high risk of diabetes, such as those with elevated body mass index (BMI). Several studies have consistently supported the idea that regular physical activity acts as a potent shield, especially for those most susceptible to this metabolic disorder.

A comprehensive review of such trials concluded that modest weight loss achieved through a combination of diet and exercise could lead to a 40%–60% reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes among high-risk individuals over 3–4 years.

Notably, this trial demonstrated that lifestyle interventions, incorporating moderate physical activity for a minimum of 150 minutes per week, surpassed the efficacy of metformin alone in reducing diabetes incidence. Strikingly, the data revealed that only seven individuals needed to undergo lifestyle intervention to prevent a single case of diabetes over three years, in contrast to 14 individuals receiving metformin.

Just two hours of walking per week was associated with a noteworthy reduction in premature death rates. Individuals with diabetes who adhered to this modest exercise regimen experienced a 39%–54% lower risk of premature death from any cause and a 34%–53% lower risk of cardiovascular disease-related mortality.

Cancer, a scourge that is as abundant as it is illusive, has also been shown to be mitigated by the power of regular exercise.

In a systematic review of epidemiologic studies, activities classified as moderate demonstrated a more substantial protective effect compared to those of lesser intensity. This insight underscores the importance of engaging in activities that elevate heart rate and metabolic demand.

Physically active individuals, both men and women, showcased a noteworthy 30%–40% reduction in the relative risk of colon cancer. Similarly, physically active women exhibited a 20%–30% reduction in the relative risk of breast cancer when compared to their inactive counterparts.

While the primary prevention of cancer through physical activity is a well-established narrative, the influence of an active lifestyle on secondary illnesses, such as cancer-related death and recurrence, is an area of emerging interest.

A recent study revealed that the most active women experienced a remarkable 26%–40% reduction in the relative risk of cancer-related death and recurrence of breast cancer compared with their least active counterparts, suggesting that the benefits of physical activity extend beyond the prevention of initial cancer development.

Recent studies have highlighted the significant role of weight-bearing exercises, especially resistance training, in improving bone mineral density (BMD). Research, including a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, shows that exercise programs can nearly reverse 1% of bone loss annually in key areas like the lumbar spine and femoral neck for both pre- and postmenopausal women.

Additionally, regular exercise training markedly reduces the risk and number of falls, a major concern for older adults. Active individuals also have a lower incidence of fractures.

In a notable 6-month RCT with 98 women, those engaged in resistance training or agility training showed significant increases in cortical bone density, whereas the stretching group experienced decreases. This study emphasizes the specific benefits of different exercise types on bone health.

Another study revealed that a 2-year intensive training program for early postmenopausal osteopenic women effectively slowed bone loss, underscoring the importance of incorporating resistance exercises into fitness routines for enhancing bone density and reducing fall and fracture risks, thereby improving the overall quality of life and bone health, particularly with aging.

Regular physical activity is not only good for the body but also enhances academic performance. Studies show that increased physical fitness can improve learning, especially in key subjects like mathematics and reading. These areas require strong executive functions—like memory, attention, and problem-solving—which are improved through physical activity.

Even short bursts of physical activity can sharpen cognitive functions and overall brain health, which are crucial for academic success. Children engaging in moderate to vigorous physical activity benefit most, showing notable improvements in attention and memory, essential for effective learning.

Incorporating physical education and active breaks into the school day can thus do more than just keep students physically fit; it can significantly boost their academic performance, highlighting the importance of a balanced approach to education, where physical and cognitive development are seen as interconnected and equally important.

While the exact “volume” of exercise needed for maximum health benefits is still debated, there are general guidelines supported by most health and fitness organizations that form a solid starting point.

A commonly recommended baseline is engaging in physical activities that expend about 1000 calories per week, a level of activity acknowledged as the minimum effective dose for noticeable health benefits, with greater energy expenditures offering additional advantages.

However, it’s important to note that any amount of physical activity is better than none. For instance, engaging in moderately intense exercises for at least 40 minutes per week can effectively prevent type 2 diabetes. Similarly, walking more than 2 hours per week has been shown to reduce the risk of premature death in those with this condition.

In cancer prevention, moderate physical activity for about 30–60 minutes daily has shown a significant protective effect against colon and breast cancer. The highest reduction in breast cancer risk is observed in women who perform seven or more hours of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity weekly. For cancer survivors, exercising at a moderate pace for 3–5 hours per week yields the greatest benefits.

The key finding, however, is that while higher levels of physical activity can offer greater health benefits, even modest amounts can make a significant difference, highlighting the importance of incorporating some form of physical activity into daily routines.

In a world increasingly burdened by chronic diseases, mental health disorders, and over-medication, the path to better health and well-being lies in our own hands. The three pillars of health – sleep, diet, and exercise – offer a powerful antidote to these growing health crises.

Sleep, often overlooked, is the foundation of good health. It’s a natural healer, crucial for cognitive function, mental well-being, and overall physical health. As research continues to unravel the intricate benefits of sleep, it becomes evident that ensuring adequate and quality sleep is not a luxury, but a necessity.

Diet, the second pillar, has far-reaching impacts beyond physical health. The emerging field of nutritional psychiatry is uncovering the deep connections between diet, mental health, and sleep quality. A shift towards a diet rich in vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and fish, as exemplified by Mediterranean-style diets, can significantly improve our physical and mental well-being. This approach to eating not only reduces the risk of chronic diseases but also fosters a healthy gut microbiome, which is essential for overall health.

Exercise, the third pillar, is a universal remedy. Its benefits extend from preventing chronic diseases like heart disease, diabetes, and cancer to enhancing cognitive functions and academic performance. The key is not necessarily the intensity or type of exercise but the consistency and integration of physical activity into our daily lives. Even modest amounts can have profound health benefits, underscoring the idea that some exercise is always better than none.

The solution to a healthier, longer life isn’t found in the medicine cabinet but in our daily choices and habits. Embracing and balancing these three pillars – sleep, diet, and exercise – can lead us to a healthier, more fulfilling life. It’s a holistic approach that not only addresses the symptoms of ill health but strikes at the root, offering a sustainable path to wellness and vitality.

While eight hours of sleep is frequently cited as a minimum, the consensus among experts across thousands of evaluations, studies, and scientific articles identifies a sweet spot for the average healthy adult of between seven and seven and a half hours.

Mediterranean-style foods such as wholegrains, fruit, vegetables, and fish are excellent for health, while processed meats, refined grains, sugar, and sodium are detrimental.

commonly recommended baseline is engaging in physical activities that expend about 1000 calories per week, a level of activity acknowledged as the minimum effective dose for noticeable health benefits, with greater energy expenditures offering additional advantages.

The benefits of grounding have been scientifically studied and include reductions in inflammation, diabetes, and stress.

Maintaining physical health is a lifelong endeavor, but there are some easy evidence-based activities that can be implemented immediately for a healthier lifestyle.

Analysis paralysis occurs when overanalyzing a situation results in a lack of ability to make a decision. These effects are worsened in those with ADHD, leading to ADHD paralysis.

Emotions stem from the limbic system, an impulsive and primal part of the brain that is extremely powerful. Unfortunately, no one teaches us how to manage emotions, but thankfully these books will.

Discover what is the ketogenic diet — a low-carb, high-fat way of eating that shifts your body into fat-burning, ketone-producing mode.

While social media can be a powerful tool, many end up abusing it to the detriment of their mental health, contributing to depression, anxiety and addiction.

© 2025 Modern Mind Masters - All Rights Reserved

You’ll Learn:

Effective Immediately: 5 Powerful Changes Now, To Improve Your Life Tomorrow.

Click the purple button and we’ll email you your free copy.