How would you know who was good if there was no evil? How would you know you were rich if you’d never seen the poor? And how would you know if you had succeeded if you had never failed?

We cannot, by definition, have success without first enduring failure. Yet every waking second of our lives seems devoted to avoiding failure at all costs. While understandable (failure often brings unpleasant feelings of guilt, regret, and embarrassment), the degree to which we take this has become extreme, unnatural, and, ironically, damaging to our future success.

Our fear of failure often stops us from even trying, whereby we fail by default. This is the “Failure Paradox”. We know some degree of failure is inevitable (much of life’s events are beyond our control), so why do we drive ourselves to such extremes to avoid what we know we are certain to confront throughout our lives?

Life is a delicate balance between risk and reward; the greater the reward we seek, the greater the associated risk (and chance of failure). Imagine then, if instead of fearing failure, you could use it to craft success? This article will explain how you can do this, and show how others have achieved incredible feats by applying the same principles.

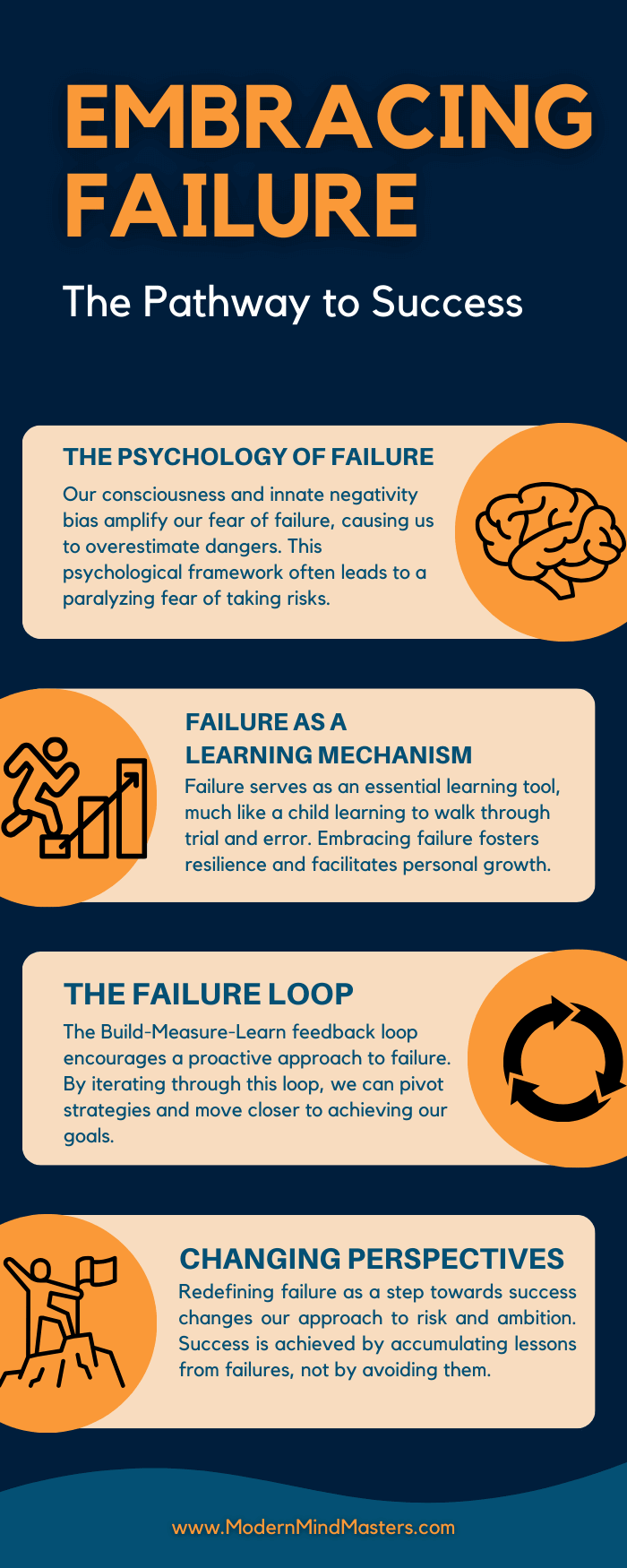

Why do we Fear Failure?

Before we dive into how we should use failure as our greatest tool for success, we must first understand the psychology behind failure and why we have become so blindly fearful of it.

Humans have been both blessed and cursed by the unique trait among living entities – the faculty of consciousness. The ability to think beyond our immediate needs has enabled humankind to invent and develop their way to emerge as the dominant species on Earth.

While we cannot outmatch the speed of a cheetah or the strength of a gorilla, we can use our consciousness and intelligence to avoid these disadvantages altogether.

Our consciousness is unique in that it can look to the future to sense potential dangers before they occur. Where many deer have walked across the road oblivious to vehicles that zoom by, humans know to look both ways before crossing. Where we know we need to keep wounds clean from bacteria for fear of infection, many animals die from small wound infections.

Unfortunately, our ability to think about potential danger is often blown way out of proportion. Our minds tend to exaggerate both the likelihood and severity of potential dangers to a point where we become paralyzed by fear.

Some fear flying despite it being the safest mode of transport, yet think nothing about driving a car which the International Air Transport Association estimated is 86 times more likely to get you into an accident.

But we cannot be completely blamed for this overreaction to danger, however, because it is completely natural and inherent in every one of our genetic structures. Yes, that’s right, it is a biological faux pas, and not a problem with you or your mentality. We call it the “Negativity Bias”.

The Negativity Bias

You will have almost certainly experienced its effects even if you’ve never been aware of it. The negativity bias defines our tendency to not only register negative stimuli more readily than positive stimuli but to also dwell on them for longer.

Road rage is a prime example. You may have had an excellent day, perhaps you made a big sale at work or received the good news that you will be getting a pay rise. It might be Friday afternoon and you are looking forward to relaxing for the entire weekend. Yet that one person who cut you off on your commute home can ruin your entire day.

You fester with anger at the injustice of someone taking advantage of you. For the next hour, you think of nothing but all of the things you wish you could have done to teach them a lesson, such as brake-checking them, lowering the window, and letting them know what you think of their driving, or perhaps even physically harming them.

Despite all the good things that happened previously in the day, and the relaxing weekend you are about to enjoy, all is soon forgotten and you now linger in negativity. Such is the power of the negativity bias.

Negativity is Natural and the Result of Primal Instincts

The bias is a primal instinct stemming from the subconscious part of the mind which we have very little direct control over. Before we evolved into conscious, modern intelligent beings (well, most of us anyway), we relied on this fight or flight instinct to keep us from harm.

For example, when a troop of Gorillas sees a cameraman trying to film a nature documentary about them, they assume they are a potential threat and instinctively show aggression.

The primal subconscious part of their brains only works in absolutes. Something has to be known to be safe, otherwise, it is assumed to be a threat. It is far safer to overestimate danger than it is to underestimate it.

So how does the negativity bias tie in with failure? Well, we know the negativity bias is nature’s way to try and keep us from harm when we haven’t the time or experience to judge something more fairly based on the facts. While this was once necessary to help us survive, in modern times it prevents us from thriving.

We are so scared of failure because of the negativity bias. If the subconscious mind cannot definitively determine whether something is 100 percent safe, it will assume it isn’t just in case. In the primal mind, the consequences of not doing so could mean death.

For example, you may be too scared to go for a promotion because you are scared of failing in front of your colleagues. Your primal mind is telling you “don’t do it, you may become embarrassed and secluded from the safety of the group”.

But your rational conscious mind is telling you “what have you got to lose? Either you get the promotion and the benefits it entails or you stay in the same position you are now, without losing anything”. By fearing applying for the promotion, you can see the subconscious mind succumb to overblown primal thoughts. For many, it may prevent them from trying altogether.

Failing to Try is Failing by Default

J.K. Rowling summed it up best:

“It is impossible to live without failing at something, unless you live so cautiously that you might as well not have lived at all – in which case, you fail by default”.

By not understanding our inherent negativity bias, we are much more likely to succumb to our negative thoughts and emotions and fail to try altogether. How many people have dreams of starting their own business or changing career paths to something that will excite them every day, but never do so for fear of trying?

When our primal subconscious mind uses the negativity bias to inflate potential dangers, we must use our conscious mind to manually change our perspective of failure. We need to avoid looking at failure as an absolute end and instead look at it for what it is, an opportunity to learn and grow. In other words, we need to learn the correct way to fail.

Failure is Nature’s Best Learning Mechanism

Benjamin Franklin once quipped, “There are only two things certain in life: death and taxes”. I would add a third – failure. Failure is a dirty word that is often taken way too seriously. It is viewed with great embarrassment, serving only to dishearten and discourage.

But failure is the catalyst for one of the most effective learning tools available to man. In fact, making mistakes is the most fundamental component of the biological learning mechanism. The primary reason humans have emerged as the dominant species is through our advanced ability to learn from mistakes.

Yet the modern person will go to extraordinary lengths to avoid failure to any degree, even to the detriment of self-improvement.

Ironically, failure is the most efficient path to success.

A child, for example, is never taught how to walk. It is an innate ability they pick up naturally by learning from trial and error.

Each trip and fall sends neurons flying around their brains, building increasingly more capable neural networks and continually strengthening the mind-muscle connection with each iteration. Each failure results in another piece of information for the central nervous system to build upon, with each failure progressing one step closer to eventual success.

Failure doesn’t faze a child learning to walk like it would an adult going through the same process. Despite taking weeks or months to progress from a cute crawling blob to a daring drunken sailor, they never stop trying.

Learning from failure is the most basic human learning trait in existence, yet by the time we reach adulthood we begin to lose this passion for learning and instead grow to fear it. It truly is one of life’s greatest wastes.

What separates a successful entrepreneur from an unsuccessful one is not a greater intelligence (although this certainly helps) but becoming an expert at failing. When failure inevitably occurs, successful people correlate this more positively, seeing it as another step closer to their ultimate goal.

Extroverts tend to find this more instinctive as they care less about what others think and are more concerned with their betterment. Introverts, on the other hand, are more likely to be influenced by what others think of them, leading them to become more risk-averse through fear of looking foolish.

The Failure Loop – Learning From Failure

One of the best books on the market for any aspiring entrepreneur is “The Lean Startup” by Eric Ries. In his legendary writings, he explains the concept of a “feedback loop” which he applies to any product or business idea to turn a profit in as little time as possible and as inexpensively as possible. This feedback loop can be applied not only to products and businesses but also to achieving our goals.

The feedback loop is a basic three-component loop; build-measure-learn. It is the framework for establishing, and continuously improving, new ideas (such as products and services) as quickly and cost-effectively as possible. The steps are explained below:

Build – In this first step of the loop, the goal is to create a Minimum Viable Product (MVP) – the most basic working prototype that allows you to test your hypothesis. For a new video streaming service, for example, it could be a basic website with just one movie.

Whatever MVP you choose, it needs to show just enough core features to attract the interest of early adopters – the people who’ll likely want to buy your product as soon as it launches. We don’t want to waste time creating the ultimate product that we think our customers would want, only for them to not want it.

Instead, we want to spend as little time and money as possible to get the bare minimum working model into the hands of those who will eventually become paying customers. The purpose of this is to learn as much as possible as quickly as possible (i.e. we get the maximum knowledge output for the minimum effort input).

Your priority, as a startup, should be to prove the demand for your proposed product and not to waste resources building a fully functioning model that’s full of advanced features that no users will end up paying for.

Measure – You can only analyze information that you have measured. Quality decisions depend on quality data. How does the result compare with your hypothesis? Is there sufficient interest in your idea to continue developing it? Does the data show that you’ll be able to build a sustainable business around your product or service?

Learn – And here is the most important step. There are two main conclusions from the loop; either your hypothesis was correct, and you persevere with the idea and continuously improve, or your hypothesis fails.

Fortunately, because you measured the information in the previous part of the loop, you should have gained valuable knowledge about what doesn’t work, which enables you to pivot your idea towards a more customer-oriented one. You now have more useful information about the market you are trying to enter.

This could be considered a failure, as you now have to change your product, but in reality, it is a huge win, because you learned more accurately about the needs and wants of your consumers. You are much closer to creating a valuable business than before you started.

And because you built your MVP, you avoided wasting time and money developing a more elaborate idea that was not important to the customer. By failing fast and efficiently you prevent a larger, more damaging failure later on. That is what success looks like to me.

Build-Measure-Learn often generates “bad” news, particularly during early cycles. You may need to pivot repeatedly before you can persevere. Pivoting can be damaging to your morale, but remember that it’s a critical part of the Build-Measure-Learn process.

Although the failure loop was written with the intent of business efficiency, it also applies to the challenges we face in our everyday lives. If we missed a sales target, we should ensure we use any measured information to learn any lessons and improve for next time. The only time we fail is when we fail to learn.

We need to shift our view of what success and failure truly look like in the practical world. In your mind, success would be your hypothesis working flawlessly. But this is your ego talking. Practically, success would be any result that provides you with information in which you can pivot or readjust towards meeting your goal.

For example, an entrepreneur may wish to open the best bakery in town, and he plans to beat his competition by offering the largest assortment of baked dishes from across the world (his hypothesis).

But the local clientele only purchases two or three familiar products (the result). Instead of continuing to encourage his customers to buy unfamiliar products, he would be better off removing the worst-selling products and promoting the best selling.

The baker has to accept that the failure of his hypothesis was not an absolute failure, but an opportunity to pivot toward greater success. He has to see the lesson learned as the success, and not the result of his hypothesis.

Related Article: History’s 3 most successful failures.

How to Overcome Failure

I’ll get straight to the point because it’s so important. Do not see failure as an absolute or as an end-point. See failure as simply one step closer to inevitable success. If you knew your dreams were exactly 24 failures away, you would be rushing to fail 24 times as quickly as possible.

Similarly, we should also adjust our view on success. Success then is simply the accumulation of just enough failures to obtain the necessary knowledge to get you to your end goal. Whether this goal is starting a business, writing a book, or completing a marathon, success will come quickest once you have made enough mistakes to learn the minimum you need to know to achieve it.

The only time failure is wasted is when we fail to learn anything from mistakes and errors. Remember from the feedback loop that learning is the key step that enables us to build a better version. And as long as the loop keeps iterating, you will keep moving closer toward inevitable success.

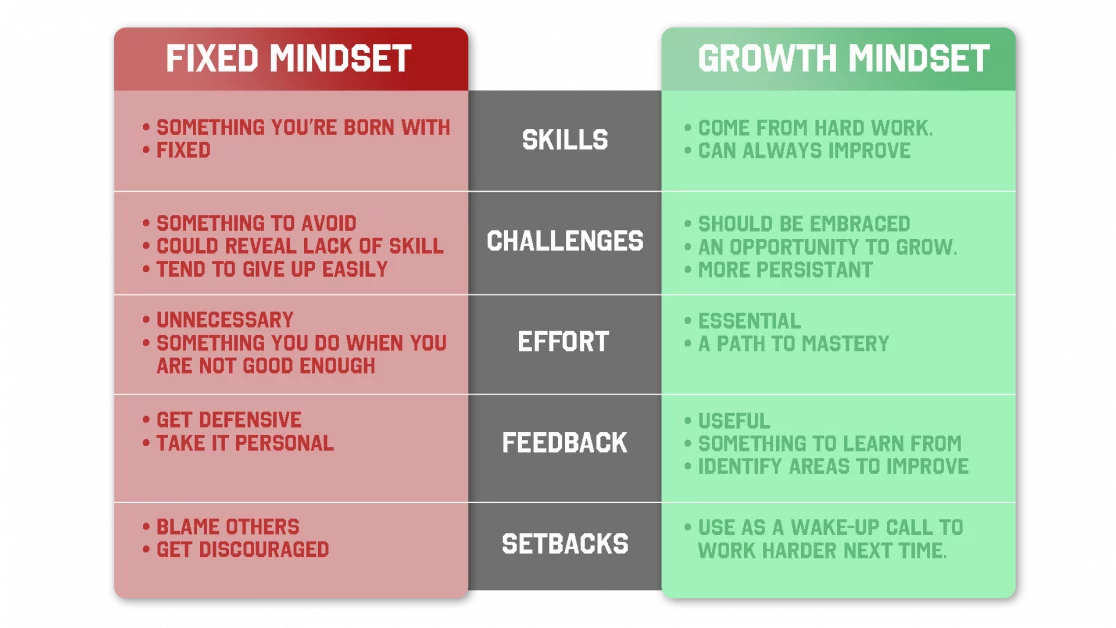

Adopt a Growth Mindset

A growth mindset is the belief that one’s abilities and intelligence can be developed through dedication, hard work, and persistence. It contrasts with a fixed mindset, where abilities are seen as innate and unchangeable.

People with a growth mindset see challenges as opportunities to learn and grow, are resilient in the face of setbacks, and believe that effort is a path to mastery. This concept, popularized by psychologist Carol Dweck, emphasizes the potential for personal and intellectual growth throughout one’s life, all of which is driven by knowledge and experience obtained from past failures.

The concept of a growth mindset is intrinsically linked to the understanding and acceptance of failure as a critical component of success. In a growth mindset, failure is not seen as a negative reflection of one’s abilities but rather as a valuable learning opportunity and a stepping stone towards achieving one’s goals.

growth mindset vs fixed mindset qualities

Conclusion

The information above is what separates a successful person from an unsuccessful one. The best of the best are not the best because they were born that way, but because they have developed a healthy perspective of failure, whether they realize it or not.

For some, the ability to override their primitive subconscious minds may come naturally to them. But it is a skill, and like any skill, it can be improved and mastered with time and experience. So starting today, I want you to make one promise to yourself.

I want you to keep the feedback loop in your mind, and whenever failure inevitably rears its ugly head, I want you to measure what went wrong and ensure you learn from it.

With this mindset, you will celebrate this failure for what it is, another step closer to your goal where others would give up and fail. And with that, success is simply a matter of when not if.

Let me know your thoughts in the comments down below!

FAQs

Why am I so afraid of failing?

Our consciousness is unique in that it can look to the future to sense potential dangers before they occur. Where many deer have walked across the road oblivious to vehicles that zoom by, humans know to look both ways before crossing. Where we know we need to keep wounds clean from bacteria for fear of infection, many animals die from small wound infections.

Unfortunately, our ability to think about potential danger is often blown way out of proportion. Our minds tend to exaggerate both the likelihood and severity of potential dangers to a point where we become paralyzed by fear.

How to get over the fear of failure?

Do not see failure as an absolute or as an end-point. See failure as simply one step closer to inevitable success. If you knew your dreams were exactly 24 failures away, you would be rushing to fail 24 times as quickly as possible.

How does failure lead to success?

Success then is simply the accumulation of just enough failures to obtain the necessary knowledge to get you to your end goal. Whether this goal is starting a business, writing a book, or completing a marathon, success will come quickest once you have made enough mistakes to learn the minimum you need to know to achieve it.